4. Network Usage

Network usage for clients became a hot topic with

Exchange Server 2010 and even more so with Microsoft Office 365.

Exchange 2010 moved the client connection point to the Client Access

Server, and that meant that, for the first time, most customers had to

use a load balancer with Exchange Server. Load balancers are required

to spread the client workload evenly across multiple Exchange Client

Access Servers. They also handle directing clients to a functioning

Exchange Client Access Server in the event of a server failure. To

scale a load balancer effectively, you need to know how much network

bandwidth it will need to handle at peak time. This is the same for

Exchange Server 2013, although you can now use a layer 4 load balancer.

However, you will still need to know how much bandwidth it will need to

handle before you purchase it.

Cloud deployments on Microsoft Office 365

bring with them a similar challenge. Your design needs to define how

much network capacity will be required to connect the clients to the

service via the Internet. Since network capacity often has to be

purchased in advance and can also have long lead times, it is extremely

important to get this scaling right to avoid poor client experience or

buying too fast an Internet connection. Yes, although you may believe

that there is no such thing as “too fast an Internet connection,”

remember that you are responsible for the budget and thus you need to

determine the difference between too fast (very expensive) and too slow

(poor user experience).

The easiest way to determine your client

bandwidth usage is via the Exchange Client Network Bandwidth

Calculator, available at the following address:

This calculator allows you to model

various user profile and client type combinations. This calculator also

accounts for time zones to accommodate users in different geographic

locations and in different time zones so that they can share the same

Internet connection or load balancer.

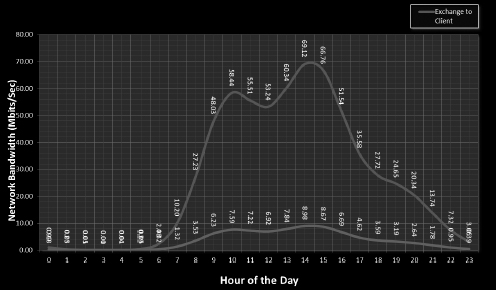

Figure 2

shows a bandwidth prediction made by the calculator. You can see that

the prediction is not a simple curve—it is based on morning and

afternoon logon peaks. In this example, which is for 53,000 light

Outlook Anywhere 2010 users, the calculator predicts that the peak

network usage will be 69.12 Mbits/sec at around 14:30 (2:30 p.m.).

Knowing not only the peak value but also the usage curve is extremely

important for network capacity planning since network links are

frequently shared with other services. To plan adequately, the network

team needs to know the quiet times as well as the peak times.

At the time of this writing, the Bandwidth

Calculator has not been updated for Exchange Server 2013. It also does

not include third-party clients such as BlackBerry OS, Good for

Enterprise clients, or Apple iOS because of constraints enforced in the

end-user license agreement for those devices. The biggest omission in

the current beta is that it does not provide data for POP3 and IMAP4.

But since the author of the calculator is also the author of this

chapter, we can say with some certainty that both POP3 and IMAP4 will

be added in the next version.

FIGURE 2 Network bandwidth prediction

5. Exchange 2013 User Throttling

User throttling was introduced in Exchange Server 2010. The fundamental idea behind user throttling

in Exchange Server is to prevent users from consuming more than their

fair share of system resources. This is intended to prevent a

denial-of-service attack and to promote fairness. If one user is using

more than their fair share of resources, then they may experience a

poor user experience. However, the rest of the users on the system will

be protected from their misuse because of user throttling.

One question that we are often asked when

discussing client scaling with customers is why didn't user throttling

protect Exchange from the iOS bug in Apple iOS 6? (iOS 6 shipped with a

bug in the way the client handled recurring meetings, which caused a

continuous synchronization loop.) The answer is that user throttling in

Exchange Server 2010 was intended to protect the system from a small

subset of users monopolizing system resources. If a large number of

users set out to monopolize system resources, the system just gets

busier and busier until throttling simply cannot protect it any further.

User throttling in Exchange Server 2010

tracked three parameters: PercentTimeInCAS, PercentTimeInAD, and

PercentTimeInMailboxRPC. When a user needed to be “backed off,”

Exchange Server 2010 would issue a delay or deny access to the user,

depending on the protocol in use. This often led to a very poor

experience and potentially even an error being displayed on the client

device. Our observations with Exchange 2010 suggest that the resource

usage limits were possibly set too high and the back-off penalties were

too severe. This meant that clients that hit the throttling limit were

likely to have a poor user experience, but also that the throttling

process did not protect the Exchange Server from misuse as well as it

should have.

Exchange Server 2013 improves

user throttling in a number of ways. First, it simply tracks the amount

of time that a user spends in the server, that is, processing time.

Second, the model for resource utilization is based on a token bucket.

This model works like a monthly salary; that is, you are given some

resources on a schedule and, if you use all of your resources too

quickly, the system will begin to throttle your connection until your

next “paycheck” when you will get some more resources. This model

allows for client bursts to take place quickly and without penalty,

but it will still control overuse by rogue clients. Third, the delays

applied by the user-throttling process are now much finer

(micro-delays). The delay applied to the user increases proportionally

to the deficit of the user, namely, the larger the resource overuse,

the larger the delay. Once the user reaches the CutOffBalance, Exchange

Server will begin to reject the user's requests. However, the client

would have to be performing very badly to reach this point.