It’s at this point that our discussion gets a bit

philosophical. There’s something of a tension between ‘audiophiles’ and

recording engineers, and it’s seems to be writ large in Pete’s world. “Whereas

the studio people, by definition, have been skeptical about the audiophile

world and not wanting to get involved, I’m in both camps. Studio people think

if you can’t measure it, it’s not there – you’re always battling against this

stuff. I think you’ve got to experiment. But the Lyric cost $19,290.08 in the

mid-fifties, which is the cost of a good house, and was built very well, and

the design is exceptional. So I’d be reticent to modify it, I don’t want this

to become an audiophile project, it needs to be about the music. The fact that

it has become an audiophile-type project has happened almost by accident.”

I put it to Pete that he’s in something of a strange

position; most studio engineers regard him as a bit bonkers thanks to his

audiophile tendencies, yet his primary motivation is not actually ‘audiophile’

as such – rather, it’s purist. “I don’t want to ‘sex the music up’, but nor do

I want it to lose its mojo! If I hear Hendrix, I want to feel like I’m in a

gritty studio someplace, not that I’m part of some corporate listening

experience, so that was the thing with these records – I wanted them to feel

like they still sounded like the originals.”

Even though he premasters vinyl, he’s rather dismissive of

this so-called black art. He prefers a more ‘hands off’ approach, resisting the

temptation to interfere with the original master tapes. “You know in the old

days, Abbey Road didn’t really add any equalization – it was frowned upon – on

classical, and even on things like The Beatles, they didn’t really add EQ and

processing. It was only in the eighties that mastering became this kind of ‘art

form’ with a ‘mastering guru’. In the old days it was more of a kind of ‘brown

coat, here-we-go’ transfer job.”

Unlike many vinyl

reissues, Pete’s come from the original master tape

As well as committing the cardinal sin of putting recordings

that were originally mastered via tube equipment through solid-state lathes,

Pete laments that vinyl reissues seem to be beset with engineers who come and

say: “Ooh, that’s a bit honky, I’ll add a bit of bass to smooth that off, add a

bit of this”. Although it might sound ‘better’, Pete reckons this isn’t right

if your goal is to retain the original sound. “So when I do the old records, I

don’t want some genius in here, putting his oar in... You know, I find

everything I hear on the reissue market sounds contemporary, a contemporary

version of a classic record. To me the music comes first, not the production.”

Press to play

We listen to Pete’s two-and-a-half grand box set through his

Garrard 301 turntable, Linn Istook tone arm and Denton DL103 cartridge running

into the mixing desk, and I point out how different it is to your average

‘audiophile’ repress. Bach’s Unaccompanied Violin Sonata has a very narrow

bandwidth, with not much up top or down below that’s of any real consequence,

yet still it sounds wonderfully engaging and open, I tell him. “Exactly, you do

feel close to the musician. It doesn’t sound like a contemporary record. I

don’t think audiophile people should really buy this. It’s quite honky!”

Pete has a strong preference for tubes over transistors, but

above this he’s a stickler for the right equipment being used for the right

period music. “I think the things to avoid if you have got a late fifties/early

sixties tape, putting it through transistor equipment, into say a Studier, you

won’t be hearing the same as you got in the original pressing, it will give you

a different sound.

I put it to him that valves also have their own problems as

well, and he retorts: “I think later valve technology isn’t as good as the

early valves, so when I hear some early stuff it’s very fast, very dynamic. But

the seventies and eighties valves have a sort of warm woolliness, which I think

people associate as ‘the valve sound’, but I don’t think it is!”

So what of the vinyl itself? Pete reckons “That whole thing

of the weight of the vinyl is a bit of a myth. Heavyweight vinyl can sound

better, but it only works on certain machines, I found, because I started

A-B’ing different test pressings and I found on some of the heavier vinyl it’s

a bit rolled-off. In terms of speed, 45RPM tends to be a bit cleaner, but it

changes the bass. You might not quite get as much of a gutsy bass – it might be

a bit more defined, but it loses a bit of charm.”

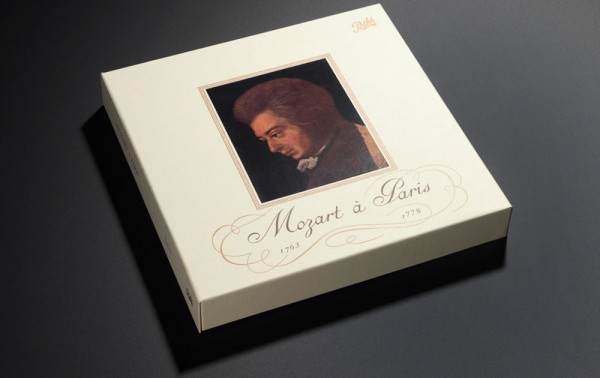

Mozart’s Complete

Parisian Compositions are a steal at $3,351.04

As far as the pressing process is concerned, Pete confesses

to be going through “a bit of a learning curve”. He’s pressed in four different

factories (in Germany, Holland, the US and UK), and they’re all very different.

“You’ve got the processing stage when you get a lacquer, then you make the

metalwork. Different people make the metalwork, and different factories make

different metalwork. There’s the various chemicals used, temperatures etc.,

expertise in different factories; then there’s the stamper and the vinyl

compound; that changes on a daily basis, and it’s different in different

countries, different suppliers. Then you’ve got the pressing machines

themselves and how they’re working on a daily basis –– whether there’s enough

heat going into the system, you might get something that’s called ‘non fill’,

which is where you get a bit of non-cyclical surface noise if the heat isn’t up

as it should be. So there’s all these variables and within that there’s the

finished product!”

Pete adds that, “I don’t evaluate the pressing on just the

surface noise. I might personally prefer a pressing that I find engaging,

dynamic, if it moves me emotionally, that has a little bit more noise – than a

flatter, quieter pressing. You can make the pressings quieter by polishing the

lacquer, but when you polish, you roll off high frequencies; so there’s all

these different variables. I’m actually having this problem right now with the

Beethoven, because I’ve got two pressings and I like both of them.”