For all but browser clients, the client

type that is deployed defines the end-user experience. It is not

unusual for Exchange Server migrations to occur and for end users not

even to notice that they have been migrated since their experience

remains virtually the same.

While not a hard-and-fast rule, the

Exchange Server software typically provides benefits in terms of

service availability and reductions in operation and deployment costs.

Client software generally provides improvements in the end-user

experience. The obvious exception to this is Outlook Web App browser

clients, because they, along with mailbox quota limits, change with

each version of Exchange deployed. It is very common for Exchange

upgrades to bring about larger mailbox sizes. It is also just as

common, however, for end users not to notice this additional space.

To achieve good Exchange design, it is

vital to bring client choice into the design process and consider the

client as part of the overall service being developed. After all, the

client is a fundamental piece of the solution.

User Experience

User experience is the term used to

describe how a user perceives the service or application that they are

using. Thus it is a somewhat subjective value where individuals may

rate their experience differently. From an Exchange client perspective,

this means that everyone may not have the same user experience with the

same client. For example, one user may be satisfied with a

super-lightweight client such as Eudora because of its simplicity and

speed, whereas another user requires features found only in Outlook

2013 for Windows.

CLIENT RESPONSIVENESS IS NOT ALWAYS AN ISSUE WITH EXCHANGE

Client responsiveness is another feature that is

often missed during Exchange service design. We witnessed a great

example of this type of omission from a customer who had deployed

Exchange Server 2010 successfully. They had increased mailbox quota

sizes from 100 MB to 5 GB by moving to Exchange Native Data Protection

and low-cost, locally attached storage. The project was thought to be a

great success by all metrics. Nevertheless, we were asked to help this

customer less than 12 months after their migration because “Exchange

was slow” and, despite their best efforts, they were unable to

determine the reason why. After a short analysis, we concluded that

Exchange was actually performing very well, even though the end users

were complaining of poor performance. Further analysis indicated that

most of the users who were complaining were using laptops with 5.4K RPM

hard disk drives and an old version of an antivirus software program.

The combination of additional disk I/O caused by the larger Outlook

cache file (.ost), slow hard

disk drives, and an overly aggressive antivirus software configuration

was causing delays of 3–5 minutes for Outlook to open, and client

responsiveness was terrible in general. The customer replaced the older

laptops, upgraded the hard drives in the newer models, and updated the

antivirus software across the board. The resulting change in user

experience was extraordinary without making any changes to the

customer's Exchange implementation.

This example is applicable for customers

moving to Exchange Online in Office 365. This service provides a 25 GB

mailbox for a very low price point. In versions prior to Outlook 2013,

the cached .ost file would

generally settle on being roughly twice the mailbox size. In the

previous case, that would mean that Outlook 2010 would require roughly

50 GB of local disk space on the client machine to cache a full 25 GB

mailbox. Outlook 2013 contains two features to help with this issue:

First, the .ost file structure

has been engineered for improved compression to avoid file growth over

time. Second, you can control the age of items that are stored in the

local cache via a slider within Outlook.

Smaller Ultrabook-style laptops are now

very popular. Their solid-state drives (SSD), however, often have a

relatively small capacity—128 GB is commonplace. This means that an end

user may run out of physical disk capacity on their laptop before they

reach their mailbox quota, which is indeed a very poor user experience!

Supportability

Supportability can be split into two areas. The

first is manufacturer support, such as Microsoft providing support for

Outlook. The second area is the ability of support personal to operate

and troubleshoot the product, such as the local help desk staff's

ability to troubleshoot Outlook connectivity issues. For the purposes

of this section, we will concentrate on manufacturer support, since the

help desk support function is unique to each environment.

OUTLOOK

Outlook has been the primary quality client for

Exchange Server since Outlook 97. Every new release of Microsoft Office

includes an updated version of Outlook that makes the best use of the

latest Exchange Server features. This development cycle has made

Outlook the most common email client in use in business today by far.

Nonetheless, with

each new release of Outlook, the testing matrix for Exchange has grown.

To combat this problem, the Exchange team made the decision starting

with Exchange 2007 to discontinue support for older versions of

Outlook. For example, support for Outlook 2000 was discontinued with

Exchange Server 2007, and support for Outlook 2002 was dropped in

Exchange Server 2010. This meant that it was necessary to know which

client versions were installed in an organization and which client

versions were supported for the version of Exchange that you were

deploying. For Exchange Server 2013, the following versions of Outlook

are supported:

- Outlook 2013

- Outlook 2010 SP1 + April 2012 CU

- Outlook 2007 SP3 + July 2012 CU

- Entourage 2008 for Mac, Web Services Edition

- Outlook for Mac 2011

The most notable absence from this list is

Outlook 2003. This version is still fairly common. Therefore, as part

of your Exchange 2013 deployment planning, you should include client

inventory and potentially a client upgrade program to remediate

unsupported Outlook 2003 clients.

Let's move on to one of the most difficult

problems to solve. Some customers have invested significant time and

money in Excel and Word macro development. Legacy macros were written

in Visual Basic for Applications (VBA). VBA was enhanced with

each new version of Office and other Microsoft applications. This can

sometimes place Exchange projects in sticky situations where customers

need to upgrade the Outlook client for Exchange support. Moreover,

upgrading Outlook generally means upgrading the entire Microsoft Office

system, and this falls right into the critical path of the Exchange

design and deployment project.

There are a couple of options available

for solving the Outlook upgrade problem. First, it is possible to

install a newer version of Outlook next to an older version of Office.

Outlook 2007 with Office 2003, for example, allows a customer with an

old desktop installation to migrate to Exchange Server 2013 without

having to upgrade the entire Office suite at the same time. This does

have its downsides, however. For example, Outlook uses the installed

version of Word for various enhanced editing functions. Mixing versions

of Outlook and Word results in the loss of automatic spell-check in the

Outlook editor, though manual spell-check is still available.

Another option is to use Outlook Web App

instead of Outlook. The problem with OWA is that it does not provide

the same feature set or user experience as Outlook connected via MAPI

or Outlook Anywhere. Most notably in OWA in Exchange 2013, you cannot

access public folders or use S/MIME certificates. In addition, there

are the usual problems of not being able to access .pst

files. Nonetheless, for some users, this may represent a better option

than running a different version of Outlook and Office on the same

system. Of course, the ideal solution is when the customer upgrades to

Office 2013 and has their macros rewritten as necessary.

OUTLOOK WEB APP

Browser support is slightly more complex in

Exchange Server 2013 than in previous versions due to the introduction

of OWA Offline Access and the removal of spell-check from OWA, relying

instead on browser-based spell-checking. All of this along with varying

browser behavior depending on operating system makes for a number of

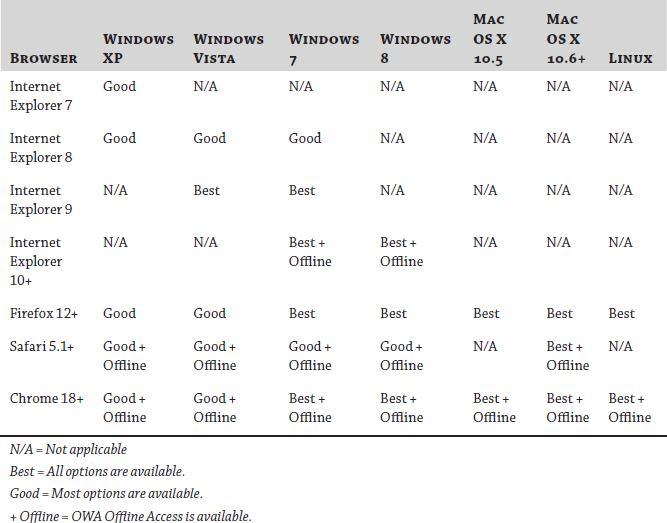

situations. Table 1 shows the relationships among browser, client, and OWA features in Exchange Server 2013.

TABLE 1: OWA feature availability by operating system and browser:

POP/IMAP

There is no specific Exchange support statement

for POP3 and IMAP4 clients from Microsoft. The only thing regarding

these clients that you need to be aware of is that, by default, both

are disabled in Exchange Server 2013. To enable POP3, you must start

the Microsoft Exchange POP3 service and the Microsoft Exchange POP3

Backend service. To enable IMAP4, you must enable the Microsoft

Exchange IMAP4 service and the Microsoft Exchange IMAP4 Backend

service. For individual client support, contact the vendor of that

client.

EXCHANGE ACTIVESYNC DEVICES

The EAS protocol version is linked to the

Exchange Server version. The latest release of EAS at the time of this

writing is version 14.1, which was last updated in Exchange Server 2010

SP1. Exchange Server 2013 and Exchange Server 2010 SP1 both use EAS 14.

This means that any EAS clients that were supported in Exchange Server

2010 SP1 are also supported in Exchange Server 2013.

By far the biggest problem with EAS

clients is determining just how many EAS features are implemented on

each device. The most comprehensive listing of EAS feature

implementation by client is found at the

following address. Nonetheless, some important client devices, such as

Windows Phone 8 and later Apple iOS versions, are missing from this

list:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_Exchange_ActiveSync_Clients

To offer any valid level of assurance that

certain devices will provide specific features given the random

behavior of EAS devices, it is imperative that you test them explicitly

to be sure.

CDO AND MAPI

As we have discussed, many third-party systems

connect via CDO and MAPI. We also noted that Exchange Server 2013 would

require a new version of CDO to connect. What we did not mention was

that manufacturers will often specify a preferred version of CDO for

each version of their product and Exchange Server to ensure the best

level of service.

We suggest that you ask your vendor to

recommend a version of CDO to use in these circumstances. They will

know best which problems they have tested for that other customers have

experienced. Never assume that simply using the latest version of CDO

will provide the best experience.

Regulatory Compliance

Compliance is a term often used during Exchange design and deployment projects. Regulatory compliance

is basically the data control processes that an organization must

follow in order to conform to the necessary laws and regulations that

govern its business.

Compliance legislation varies by country.

In the United States, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) is the

legislation cited most often that impacts Exchange. In the United

Kingdom, the Data Protection Act of 1998 applies to every organization.

In Canada, the Keeping the Promise for a Strong Economy Act (known as

C-SOX) of 2002 applies.

These pieces of legislation have many

areas in common. Most enforce rules for data retention,

confidentiality, and the release of information. It is also worth

noting that many organizations will add their own compliance polices to

maintain reputational integrity and to secure sensitive data. These

policies may state that the end user's device must be company owned or

that certain data on mobile devices must be encrypted.

It is important to understand what

legislative compliance requirements apply for each customer and where

the design will meet them; that is, on the Exchange server side or

client side. Many of the legislative compliance requirements can be met

by using journaling at the server side. Journaling keeps a

digital record of every email communication between users, both inside

and outside the organization. The client is generally not aware of this

process, and even if the client deletes content, it will remain in the

journal repository until such time that it is deleted.

Organization Security Compliance

For organizational compliance requirements such

as protecting against data leakage, the issues become more complicated.

For example, many organizations wish to control where their data is

stored and accessed. This control may include statements such as

“mobile devices must have a passcode,” “mobile devices must be

encrypted,” or “only company-provided devices are allowed to connect to

the company email system.” Such controls often provide the largest

hurdles to design teams.

We have already discussed EAS and that

although the protocol includes many security policies, the vendor of

the device chooses how these policies are implemented. This means that some

devices may report that they have met all of the security policy

requirements when in fact they have not. This was very common in early

Android devices, although most devices today are pretty good in this

regard. Additionally, controls to prove that a device is indeed company

owned may bring with them complex and expensive dependencies, such as

IPSec deployments or certificate-based authentication.

Organizations may even enforce two-factor authentication (2FA)

for system access. 2FA indicates the control of system access by

requiring two bits of authentication data. For example, your username

and password plus a security token or smartcard is two-factor

authentication. A 2FA system is perceived as being more secure than a

single-factor scheme, such as a simple username and password security

system, but it obviously brings with it more complexity. Most

significant from an Exchange client perspective, many common clients,

such as Outlook, do not support 2FA particularly well, if at all.

Given all of this doom and gloom, how

should you best meet these security requirements while simultaneously

not incurring a huge expense or making system access too difficult for

end users? The most common answer to this question is to use information rights management (IRM).

IRM works by digitally encrypting and controlling end-user rights at

the time the document or message is created. These controls allow

variations in end-user permissions such as read-only, do not forward,

block copy and paste, and disable print. The end user must authenticate

to the IRM service, which in turn will provide the information required

to decrypt the message and enforce the granted rights. Using IRM

provides many benefits, both internally and externally. From an

Exchange client perspective, the most important benefit is that as long

as your client is capable of viewing the IRM protected documents, you

no longer need to provide client-side access controls.

As a general rule, do not attempt

to control data leakage via perimeter controls and device access

solutions. Use an IRM product instead, such as Active Directory Rights

Management Services from Microsoft.