6. Prevent Changes to a Registry KeySecurity

has always been one of Microsoft's favorite marketing buzzwords, and

never more so than when Windows Vista was introduced. But as it turns

out, Vista's security features are quite a bit more useful for

protecting your PC from itself than from any alleged intruders. This feature is tremendously important, yet

most people don't even know it's there. It means you can lock a Registry

key to prevent employees from installing software on a company PC, or

prevent kids from disabling parental controls on a family PC.

Permissions also let you lock file type associations , preventing other applications from changing them. And by

locking certain other keys, you can help protect your PC from viruses

and spyware. Here's how you do it: Open the Registry Editor, and navigate to the key you want to protect. You

can't protect individual values, but rather only the keys that contain

them. This means that if you lock a key to protect one of its values,

none of its values can be modified. You can, however, choose whether or

not your changes are made to the subkeys of the selected key. |

|

Right-click the key, and select Permissions. Click Advanced, and then click Add. If the Add

button is disabled (grayed out), you'll have to take ownership of the

key, close the Permissions window, and then reopen it before you can

make any changes to the permissions of this object. |

|

In the Enter the object names to select field, type Everyone, and then click OK.

(The "Everyone" user encompasses all user accounts, including those

used by Windows processes and individual applications when they access

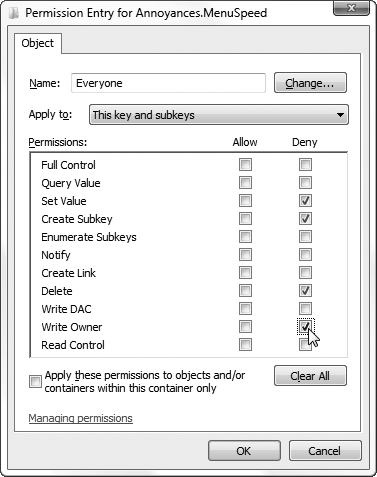

the Registry.) In the next window, "Permission Entry for...", click the checkbox in the Deny column, next to the actions you want to prohibit, as in Figure 5. See below for examples.

When you're done, click OK in each of the three open dialog windows. The change will take effect immediately.

Now, you may be tempted to remove Allow permissions for a particular user (or even all users), rather than add the Deny

entry shown here. The problem is that doing so wouldn't prevent an

application or Windows from taking ownership or adding the necessary

permissions and breaking your lock. Furthermore, it would make it much

more difficult to restore the old permissions should you need to remove

the lock; using this procedure, all you need to do is remove the Deny

rule and you're done. This works because Windows

gives Deny rules priority over Allow rules, which means you can lock a

key even if there's another Allow rule that expressly gives a user

permission to modify the item. So, which keys do you lock, and which actions do you forbid? Here are some examples:

Make a read-only key.

To lock a value yet still allow applications and Windows to read it, place a Deny checkbox next to Set Value, Delete, and Write Owner, as in Figure 3-10.

Create a complete lock-out.

To prevent all applications from reading, modifying, or deleting a value, place a Deny checkbox next to Full Control.

Keep away ShellNew.

To prevent applications from making new keys under the selected key, place a Deny checkbox next to Create Subkey.

For instance, you can do this to file type keys to prevent applications from adding themselves to Windows

Explorer's New list.

Enforce security policies.

To prevent another user from modifying a security policy , to locate the corresponding key in the Registry. Then, instead of adding a Deny

rule to the key as described above, remove any permissions that allow

anyone other than an administrator to delete, modify, or add subkeys to

the key. Make sure that there's still at least one rule for the

Administrators group (or at least your own administrator-level account)

that affords Full Control.

7. Back Up the RegistryIn

a way, the Windows Registry is a weak link in the operating system's

stability and robustness. It's remarkably easy to damage, but very

difficult to repair. And unless you go to the trouble of making your own

backup copy, it's not necessarily easy to replace it if it's damaged

(unlike, say, DLLs, which can be pulled right off the Vista CD). A

broken Registry—either due to physical corruption or errant data—might

cause Windows to behave eratically (or more so than usual) or it may

prevent Windows from starting at all. The System Protection feature is found in Control Panel → System → Advanced system settings → System Protection tab. Windows automatically creates a restore point

once a day, plus each time you install an application, device driver,

or any update from Windows Update. Restore points contain essential

Windows system files and Registry settings, although it's not clear how

much of the Registry is backed up, nor is it possible to restore all or

part of the Registry alone. |

|

So,

what's the big problem? Why not just zip up the Registry files or copy

them to a CD? The files that contain your Registry data (called hives)

are constantly being read from and written to, so Windows locks them to

ensure they can't be modified, deleted, or even read directly. This

means you have to use a procedure like the following if you want a

backup you can create and restore at will. You may want to do this, for

instance, just before you install a new program or device driver. Open Registry Editor, and collapse all the branches so only the five main root keys are showing. Highlight HKEY_CURRENT_USER. From the File menu, select Export. From the Save as type list, choose Registry Hive Files (*.*). Type a filename, and give it the .hive filename extension (e.g., hkey_current_user.hive). RegEdit won't do this for you, nor will Windows recognize the .hive

extension by default, but it will make the files much easier for you to

identify than if they have no extension, which is the default. Choose a folder to store the backup, and click Save. Next, highlight HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, and repeat steps 3–6. Make sure to choose a different filename for this branch (e.g., hkey_local_machine.hive). To restore either or both of these backups, and replace the current Registry with the data in your backup hive files, select Import from the Registry Editor's File menu. Select Registry Hive Files (*.*) from the unlabeled listbox next to the File name field, select the .hive file to import, and click Open.

There are two things worth noting about this backup procedure. First, it makes use of Registry hive

files, which are binary files, and the same type of file Windows uses

to store the Registry it uses day-to-day. If you were to instead export

ordinary Registry patch files—which is what you'd get if Registration Files (*.reg)

was selected in step 4—then you'd end up with files that couldn't be

easily restored back into the Registry. This is because the Registry

Editor only merges patch files with existing Registry data, which can leave errant data intact. When the Registry Editor imports hive files,

however, it deletes the existing keys from the Registry before bringing

in the new (backed-up) data. Registry patches can be handy for backing up individual keys, as explained in the upcoming sidebar, "The Local Backup." |

|

The

easiest type of Registry backup to make is the local backup, akin to

the local anesthetic. Rather than backing up the entire Registry, you

simply back up the portion you'll be working on. If you screw up, you

can quickly and easily restore the affected keys without touching

anything else. Say you want to make some changes to the key, HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run,

which happens to be responsible for running programs when Windows

starts. Just open the Registry Editor, navigate to this key, and select File → Export. Type a filename and save the Registry patch file on your Desktop. Make

a mistake and want to restore the backup? Just delete the key(s) you

changed, and double-click the Registry patch to load it back in. Of

course, Registry patch files can be hard to keep track of, particularly

if you change a setting and only discover two weeks later that it's

caused a problem. In this case, you can make an easy-to-find backup

right in the Registry. Before you make any changes

to the Registry, make a patch file as just described. Then, rename the

key in which you'll be working by adding .backup to the end of the key name. For instance, if you want to make a change to: HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

Highlight the Run key, press the F2 key (or right-click and select Rename), and change the name to: HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run.backup

Then, immediately reimport the Registry patch you just made, and delete the .reg patch file. You'll end up with two identical keys right next to each other: HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run.backup

At this point, you can go ahead and mess with the Run key to your heart's content, and even use the nearby Run.backup key as a handy reference. If you ever need to restore your backup—either today or six months from now—just delete the Run key and then rename Run.backup to Run. |

Second, notice that only HKEY_CURRENT_USER and HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE are backed up here, leaving HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT, HKEY_USERS, and HKEY_CURRENT_CONFIG seemingly unprotected. This is done because the data in HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT and HKEY_USERS is duplicated in the first two root keys (HKLM and HKCU, respectively) and HKEY_CURRENT_CONFIG is dynamically generated and not stored on the hard disk at all. Now,

other than saving time by not exporting more than you have to, why is

it important to know how Windows stores the Registry data? Because if

you use a slightly more advanced approach when you back up the Registry,

you'll have a backup you can restore even if Windows won't start. Here's how you do it: Open a plain-text editor (e.g., Notepad). Type the following into a blank document: if exist C:\Backups\COMPONENTS.OLD del C:\Backups\COMPONENTS.OLD

if exist C:\Backups\SAM.OLD del C:\Backups\SAM.OLD

if exist C:\Backups\SECURITY.OLD del C:\Backups\SECURITY.OLD

if exist C:\Backups\SOFTWARE.OLD del C:\Backups\SOFTWARE.OLD

if exist C:\Backups\SYSTEM.OLD del C:\Backups\SYSTEM.OLD

if exist C:\Backups\NTUSER.OLD del C:\Backups\NTUSER.OLD

ren C:\Backups\COMPONENTS COMPONENTS.OLD

ren C:\Backups\SAM SAM.OLD

ren C:\Backups\SECURITY SECURITY.OLD

ren C:\Backups\SOFTWARE SOFTWARE.OLD

ren C:\Backups\SYSTEM SYSTEM.OLD

ren C:\Backups\NTUSER.DAT NTUSER.OLD

REG SAVE HKLM\COMPONENTS C:\Backups\COMPONENTS

REG SAVE HKLM\SAM C:\Backups\SAM

REG SAVE HKLM\SECURITY C:\Backups\SECURITY

REG SAVE HKLM\SOFTWARE C:\Backups\SOFTWARE

REG SAVE HKLM\SYSTEM C:\Backups\SYSTEM

REG SAVE HKCU C:\Backups\NTUSER.DAT

Save the file somewhere convenient, such as your desktop, and give it the .bat filename extension (e.g., back up registry.bat). Open Windows Explorer, open the Computer branch, and select drive C:. Create a new folder in C:\ named Backups. If you want to store the backup hive files in a different location, replace all 24 instances of C:\Backups in the listing in step 2 with the full path of your backup folder. To run the backup, just right-click the back up registry.bat file and select Run as administrator. To run this backup automatically every time you start Windows, create a shortcut to the back up registry.bat file in your Startup folder in your Start menu. Or, if you typically hibernate your PC instead of shutting down, use the Scheduled Tasks feature to schedule the backup to run at regular intervals, say, once every three days. |

|

At this point, you can be extra compulsive and copy the backed-up hive files to a CD or network drive for safekeeping.

So, what's different about this second procedure? For one, it's automated, using the little-known REG.exe command-line Registry tool instead of the Registry Editor to create the hive files. (To learn more about REG.exe, open a Command Prompt window, type reg /? and press Enter.) Also, it automatically archives the last backup, thus maintaining two sets of backup files at all times, a feat accomplished by some simple batch-file commands . Most importantly, though, it creates five separate hive files from the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE branch—one for each sub-branch except HARDWARE,

which is dynamically generated—instead of just one. As a result, the

backup files you'll end up with are the same as those Windows normally

uses to store the Registry on your hard disk. Windows stores the active hive files—those for HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, at least—in the \Windows\System32\Config folder. The exception is the HKEY_CURRENT_USER branch, stored in the NTUSER.DAT file located in the user's home directory (usually \Users\{username}). In your snooping, you might discover the \Windows\System32\config\RegBack folder. Check the dates of the files in the RegBack folder, and sure enough, you'll see that they're recent—perhaps with yesterday's or today's date—backups of your HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE hive files. Although Vista indeed regularly creates these backups, they're neither complete (the HKEY_CURRENT_USER

branch isn't included) nor as useful as a backup you make yourself. For

instance, a problem that prevents Windows from loading is likely to

have made its way to the automatic backups, but not the manual backup

you made three days ago, just before you installed an application. |

|

All of this means that you can restore your Registry from the backup in a variety of ways. Of course, you can always use File → Import in Registry Editor,

as described earlier in this section, but that only works if Windows is

running. If Windows won't start, though, here's how to restore your

Registry from the six hive backups: Insert your Windows Vista setup disc in your drive, and start your PC.

Click Next on the first Install Windows screen, and then click Repair your computer on the second page. On the System Recovery Options window, select Microsoft Windows Vista in the list and then click Next. In the Command Prompt window that appears, type the following commands to rebuild your Registry from your hive files: REG RESTORE HKLM\COMPONENTS C:\Backups\COMPONENTS

REG RESTORE HKLM\SAM C:\Backups\SAM

REG RESTORE HKLM\SECURITY C:\Backups\SECURITY

REG RESTORE HKLM\SOFTWARE C:\Backups\SOFTWARE

REG RESTORE HKLM\SYSTEM C:\Backups\SYSTEM

REG RESTORE HKCU C:\Backups\NTUSER.DAT

You can omit one or more of these lines if you only want to restore part of the Registry. |

|

When you're done, pop out your Vista setup disc and restart your PC.

With

any luck, Windows should start normally. If it doesn't, either your

most recent backup is defective, or the problem lies elsewhere. If you

suspect that an older backup may work where the newer one failed, add

the .OLD filename extension to each filename in step 5 above, like this: REG RESTORE HKLM\COMPONENTS C:\Backups\COMPONENTS.OLD

If Windows still won't start at this point, try reinstalling Windows . Now, there's a chance that the REG.exe tool won't work, which might happen if your Registry is sufficiently corrupted or if the REG.exe file itself is damaged. In this case, try replacing the active hive files with your backups, like this: Open the Command Prompt as instructed in steps 1–4 above. Type these commands to copy the files: copy C:\Backups\COMPONENTS C:\Windows\System32\Config

copy C:\Backups\SAM C:\Windows\System32\Config

copy C:\Backups\SECURITY C:\Windows\System32\Config

copy C:\Backups\SOFTWARE C:\Windows\System32\Config

copy C:\Backups\SYSTEM C:\Windows\System32\Config

copy C:\Backups\NTUSER.DAT C:\Users\your_user_folder

where your_user_folder (on the last

line) is the name of your user folder, which may or may not be the same

as your user name. If you don't know the folder name, type dir c:\users to list all the user folders on your PC. If your user folder name has spaces in it, add quotation marks, like this: copy C:\Backups\NTUSER.DAT "C:\Users\Phillip J. Fry"

When you're done, pop out your Vista setup disc and restart your PC.

|