Digital Camera Technology

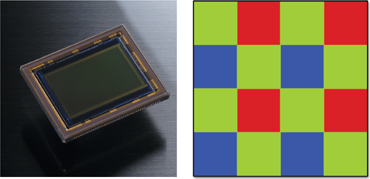

Shooting a photo

digitally produces a less accurate image than scanning a photo shot on

film with a flatbed scanner using a high spi setting. This is because

digital cameras capture data using photosensitive electronic sensors.

These sensors record brightness levels on

a per-pixel basis. However, the sensors are usually covered with a

patterned color filter that has red, green, and blue areas. Although the

filter attempts to capture all detail that the lens sees, it is unable

to completely do so due to its design.

A

CMOS sensor (left), such as this one from Nikon, is the standard

imaging device on a digital camera. The Bayer filter arrangement (right)

uses red, green, and blue pixels and is very common in digital cameras.

The filter used is

typically the Bayer filter arrangement, which contains two green pixels,

one red pixel, and one blue pixel. The Bayer filter uses more green

because the human eye has an increased sensitivity to green. This filter

allows the image to record the brightness of a single primary color

(red, green, or blue) because digital cameras work in the RGB color

space.

Not all the properties of

film can be fully imitated by the computer sensors in a digital camera,

so the camera must interpolate the color information of neighboring

pixels. This averaging produces an anti-aliased image, which can show

visible softening. When anti-aliasing is present, hard edges are blended

into one another. Sometimes this can be desirable (with low-resolution

Internet graphics where you reduce file size by limiting color). Other

times, anti-aliasing can produce an undesirable softness when you print

an image. Depending on the colors in the original image, a digital

camera might only capture as little as one-fourth of the color detail.

For example, if you had a desert scene with lots of red detail and

little green or blue, the sensor would rely on the red areas of the

filter (which only cover a fourth of the sensor face).

Does this mean you should

shoot film only? Of course not; I shoot both. But it’s important to

shoot for what you need. There are strengths and weakness of both film

and digital capture (as well as several stylistic decisions).

Ultimately, film captures a high-quality image that can be optically

enlarged using the negative. However, digital capture can be more

convenient and affordable because you get instant feedback on the images

you have just taken, and you eliminate the time-consuming process and

costs associated with developing the film.

It

is important to shoot at a high pixel count (which can be accomplished

by setting the camera to shoot in a high- or best-quality mode). You can

always crop or shrink the image for output or display, but you should

avoid enlarging the image if you don’t have to. When a digital image is

enlarged, it can create unwanted image softness or pixelization (a

visible blockiness). Capture as much pixel data as possible to minimize

digital upsampling (increasing the resolution of the image).

Shooting JPEG vs. Raw

When digital cameras

became commercially available, the memory cards used to store pictures

were very expensive. Many photographers could not afford multiple or

high-capacity cards, so they wanted more images to fit on a single,

smaller card. Many users also emailed their pictures to friends and

family. Small file sizes enabled consumers who lacked an understanding

of digital imaging to attach photos to emails with minimum technical

headaches. With these two scenarios in mind, manufacturers turned to an

Internet-friendly format, JPEG (Joint Photographic Experts Group). It

was a proven technology and one that was familiar to many users.

The JPEG format is

extremely common because most hardware and software manufacturers have

built support for it into their products. The JPEG format is also

extremely efficient at compressing images, and it is a good format for

continuous tone images, such as photos. A JPEG file looks for areas

where pixel detail is repeated, such as the color blue in a photo of the

sky. The file then discards repeated information and tells the computer

to repeat certain color values or data to re-create the image.

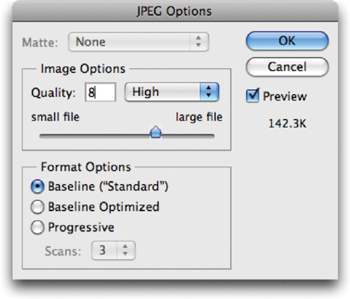

The

JPEG Options dialog box is available when you modify a JPEG file with

Photoshop. When saving, you can adjust the Quality slider to reduce file

size. It is best to leave Quality set to maximum if you will be making

future edits to the image: This applies the least compression that could

damage the image’s appearance.

Although JPEG is a good

format for distributing images (due to their compatibility and small

file size), it is not great for image acquisition or production. A JPEG

file is lossy, meaning that every time you modify it in Photoshop and

resave as a JPEG,

additional compression is applied to the image. Over subsequent

compressions, the image quality can noticeably deteriorate. This is

similar to the act of making a photocopy of another photocopy:

Additional image deterioration occurs with each processing step. The

visible loss in image detail or accuracy is referred to as compression artifacts.

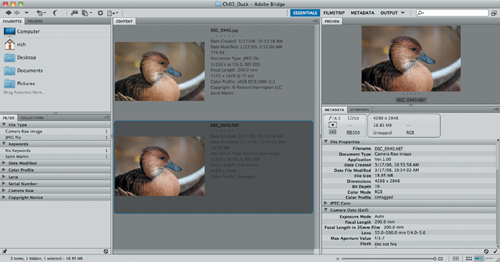

This

image was captured as both a raw and a JPEG file when it was shot. The

picture was taken with a Nikon D300, which can simultaneously write both

files to the memory card when shooting.

So, if JPEG is inferior,

why do so many people use it? Money and resistance to change are the

simple answers. It’s a lot cheaper to shoot JPEG images because you

don’t need to buy as many memory cards. Certain scenarios like sports

and photojournalism often rely on the speed associated with smaller

files as well. Additionally, even many pros have been slow to abandon

JPEGs due to fear of change. Learning how to use new technology requires

time, something that most people are short of these days.

Tip: Workaround for Unsupported Cameras

If Photoshop does not

support a particular raw format used by your camera, use the software

that shipped with the camera. The image can be converted into a 16 bit

TIFF image (a high-quality file with no compression), which Photoshop

can open.

Newer digital cameras,

generally the pro models, offer newer formats, typically called raw.

These raw (or native) formats have several benefits over shooting to

JPEG. The images are usually captured at a higher bit rate, which means

that the pixels contain more information about the color values in the

image. Most raw files have a depth of 10, 12, or even 16 bits per

channel instead of the 8 used by JPEG. The raw format also has a greater

tonal range; hence, there is a better exposure for shadows and

highlights. This extra information makes your

work in Photoshop easier because it adds greater flexibility and

control in image adjustments and color correction. You should have less

work to do in Photoshop as well, because the image captured has more

color information than a JPEG would have.

Raw files can be two to six

times larger than JPEG files. This extra data is used to hold more image

detail, which can reduce, or even eliminate, compression artifacts

found in JPEG files. However, that extra data can increase the time it

takes for the files to write to the memory card.

Tip: Camera Raw for TIFF and JPEG?

Although the Camera Raw

interface can be used for JPEG and TIFF files, those images have already

had the camera’s processing permanently applied to the image. Shooting

raw has many benefits and should be fully explored by reading the

documentation that accompanies your camera.

The raw file captures

the unprocessed data from the camera’s image sensor. Although your

camera may contain settings for sharpness, exposure, or lighting

conditions, the raw file stores that setting as modifiable information

and captures the original (unmodified) data that came through your

camera’s sensors. This is very useful because it lets you easily adjust

white balance within Photoshop. Each manufacturer treats the format

differently, using a proprietary format. Fortunately, Photoshop

frequently updates its raw technology to support the newest cameras on

the market. To find out if you can access a particular camera format

from within Photoshop, visit Adobe’s Web site at www.adobe.com/products/photoshop/cameraraw.html.

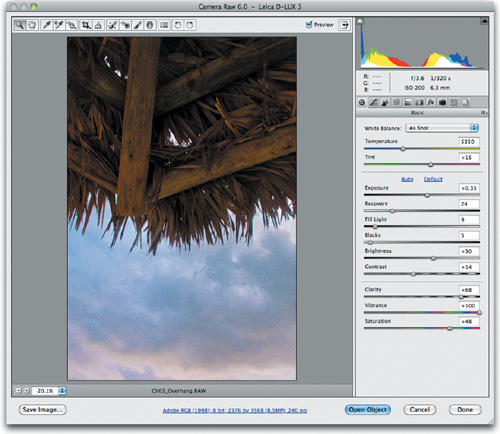

Because the raw data is

unprocessed, you must essentially “develop” the image data inside

Photoshop. You’ll be presented with several choices when opening a raw

image. You can choose to adjust several options related to the image, as

well as the lens and lighting conditions. All the adjustments made in

the Camera Raw dialog box are nondestructive, meaning the original image

is preserved in pristine condition. You can “tweak” the image after

shooting it, including being able to easily save those changes and apply

them to similar exposures.

The

Adobe Camera Raw dialog box is a versatile environment for “developing”

your pictures. The image Ch03_Overhang.RAW is included on the DVD.

Choose File > Open and navigate to the file . In Photoshop CS5, you can even make localized adjustments by

painting an area to select it and then use sliders to modify it.

The Camera Raw dialog box has continued to evolve since it

was first introduced as a purchased add-on to Photoshop 7. Subsequent

versions of Photoshop have updated the user interface. Be sure to watch

my detailed video tutorial to learn more about this powerful developing

tool. Fortunately, the Camera Raw dialog box is fairly intuitive,

especially once you understand the concepts of adjusting images.

|

In 2004 Adobe released the

Digital Negative Specification (DNG) file format. The code and

specifications were made publicly available so manufacturers could build

support for the format into their products. The goal was to replace

several proprietary raw file formats with a universal format. Despite

initial optimism, camera manufacturers have been slow to adopt it (some

even refusing). At this point, DNG files are a useful way to archive raw

files and attach additional metadata. You can find out more about DNG

by visiting Adobe’s Web site at www.adobe.com/products/dng/main.html.

|

Acquiring Images from a Digital Camera

There are two major ways of

downloading images from a digital camera. Which connection type you

choose will depend on your work environment and budget for additional

hardware.

Tip: Make Backup Copies

You may want to work with a

copy of your transferred image, especially if you are just getting

started in Photoshop. Many users will duplicate a folder of images and

work with those. Others will burn a copy of the original images to a CD

or DVD for backup. Preserving an original digital file is a good idea

for future use. If you are shooting raw, there is no need to duplicate

the raw file. The modifications to the image are stored in a separate

sidecar file in the folder with your images.

The first method involves

plugging the camera directly into the computer. Many cameras ship with a

connecting cable (generally USB). The advantage of this approach is

that it doesn’t require an extra hardware purchase. The primary

disadvantages of this method are that it ties up the camera, and it is

hard on delicate ports built into the camera. If you break the USB port

by constantly plugging in and unplugging a camera, it can lead to an

expensive service bill. The data port is interconnected with several

other systems on the camera; a break at one end can result in problems

in other areas. Additionally, if the camera’s battery were to be

depleted during image transfer, the memory card and its contents can

become corrupt.

A better option for

downloading images from a digital camera is to purchase a stand-alone

memory card reader. There are many options available, so consider these

questions and choose wisely:

Do you need only one card format, or do you need to read multiple formats?

Do you want a read-only device, or do you want to be able to erase and reformat cards while they are in the reader?

How

fast do you want your files to transfer? Be wary of card readers that

are USB 1, which can take a long time to transfer files. Look for USB 2,

USB 3, FireWire, or eSATA for faster data rates. Laptop users with a

card slot can purchase an effective card adapter for fast file transfers

without tying up ports.

Do

you want to transfer multiple cards at once? Some readers allow for two

or even four cards to be mounted at one time so you can initiate a

large transfer and walk away.

Note: Transferring Files

The

actual transfer of photos is not handled by Photoshop. Rather, you can

use Adobe Bridge CS5, which includes a Photo Downloader (File > Get

Photos from Camera). If you are not using Bridge, the files are handled

natively by your computer’s operating system. Just manually copy them to

a folder on your computer.