What constitutes an “optimized” clip? What makes a

color-corrected image correct? Let’s look at what is typically “wrong”

with source footage levels and the usual methods for correcting them, in

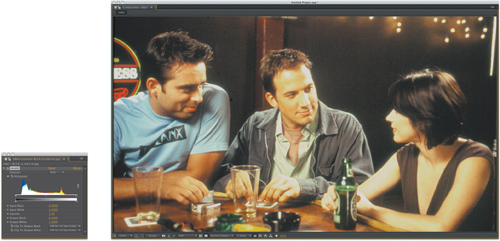

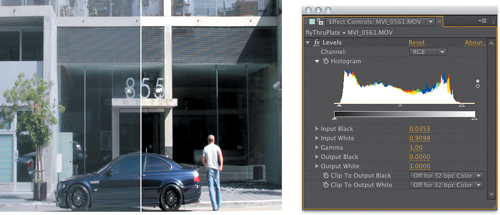

order to lay the groundwork for color matching. As an example, let’s

look at brightness and contrast of a plate image, with no foreground layers to match.

Notes

The term plate

stretches back to the earliest days of optical compositing (and indeed,

of photography itself) and refers to the source footage, typically the

background onto which foreground elements will be composited. A related

term, clean plate, refers to the background with any moving foreground elements removed. |

Levels

Levels may be the most-used

tool in After Effects. It consists of five basic controls—Input Black,

Input White, Output Black, Output White, and Gamma—each of which can be

adjusted in five separate contexts (the four individual image channels

R, G, B, and A, as well as all three color channels, RGB, at once).

There are two different ways to adjust these controls: via their

numerical sliders or by dragging their respective caret sliders on the

histogram (which is the more typical method).

Contrast: Input and Output Levels

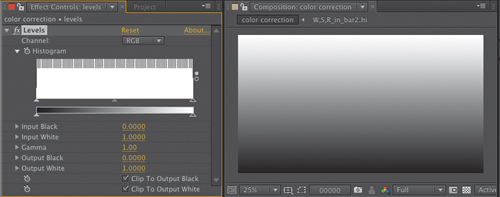

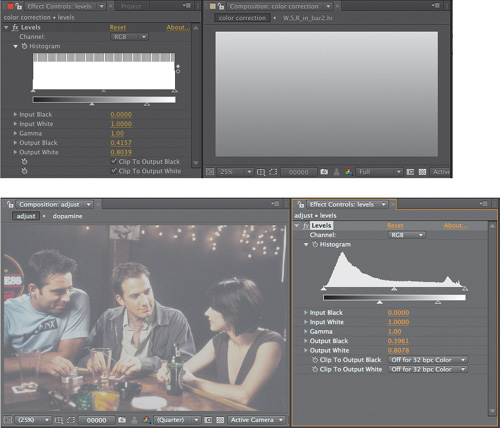

Four of the five controls—Input Black, Input White, Output Black, and Output White (Figure 1)—determine

brightness and contrast, and combined with the fifth, Gamma, they offer

more precision than is possible with the Brightness & Contrast

effect.

(Image from the film Dopamine, courtesy of Mark Decena, Kontent Films.)

Figure 2

shows a Ramp effect applied to a solid using the default settings,

followed by the Levels effect. Move the black caret at the lower left of

the histogram—the Input Black level—to the right, and values below its

threshold (the numerical Input Black setting, which changes as you move

the caret) are pushed to black. The further you move the caret, the more

values are “crushed” to pure black.

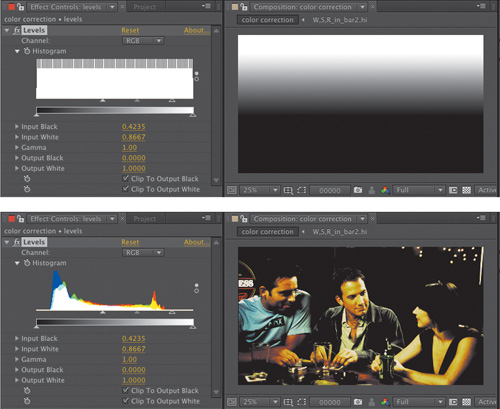

Move

the Input White caret at the right end of the histogram to the left,

toward the Input Black caret. The effect is similar to Input Black’s but

inverted: More and more white values are “blown out” to pure white (Figure 3).

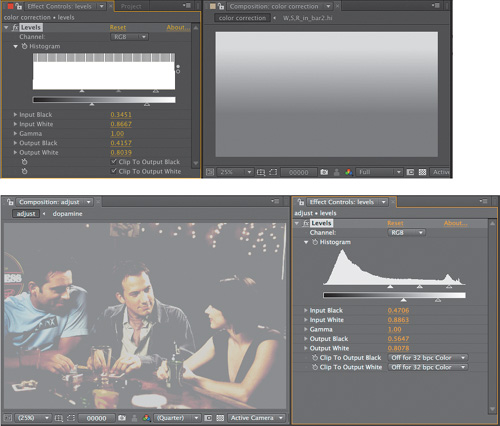

Either adjustment

effectively increases contrast, but note that the midpoint of the

gradient also changes as each endpoint is moved in. In Figure 3,

Input Black has been adjusted more heavily than Input White, causing

the horizon of the gradient to move closer to white and the shadows to

darken. You can re-create this adjustment with Brightness & Contrast

(Figure 4), but there’s no direct control of the midpoint (gamma) of the image (Figure 5).

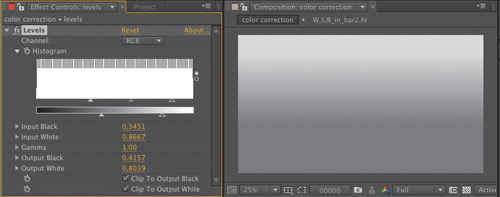

Reset

Levels (click Reset at the top of the Levels effect controls) and try

adjusting Output Black and Output White, whose controls sit below the

gradient. Output Black specifies the darkest black that can appear in

the image; adjust it upward and the minimum value is raised.

Tip

You can reset any individual effect control by context-clicking it and choosing Reset. You know it’s an individual effect if it has its own stopwatch. |

Lowering Input White is

something like dimming the image, cutting off the maximum white value at

the given threshold. Adjust both and you effectively reduce contrast in

the image. Bring them alongside one another, and the gradient becomes a

solid gray (Figure 6).

So

Input and Output controls have inverse effects. But you will find

situations where you might use them together, first balancing the image,

then reducing contrast in the whites, blacks, or both.

As is the case

throughout After Effects, the controls operate in the order listed in

the interface. In other words, raising the Input Black level first

raises black density, and a higher Output Black level raises all of the

resulting black levels together (Figure 7).

If you’ve crushed the blacks with Input Black they remain crushed, and

they all just appear lighter.

If you’re thinking, “So what?” at this point, just stay with this until we move to a situation in which to apply it.

Brightness: Gamma

As you adjust the Input Black

and White values, you may have noticed the third caret that maintains

its place between them. This is the Gamma control, affecting midtones

(the middle gray point in the gradient) without touching

the white and black points. Adjust gamma of the gradient image and

notice that you can push the grays in the image brighter (by moving it

to the left) or darker (by moving it to the right) without changing the

black and white levels.

Many images have healthy

contrast, but a gamma boost gives them extra punch. Similarly, an image

that looks a bit too “hot” may be instantly adjusted simply by lowering

gamma.

In most cases, the image itself

rather than the histogram offers the best clue as to whether the gamma

needs adjustment.

So what is your guideline for how much to adjust gamma, if at all? I

first learned always to go too far before dialing back, which is

especially helpful when learning. An even more powerful gamma adjustment

tool that scares novices away is Curves (coming up).

Close-up: What Is Gamma, Anyway?

It

would be nice but inaccurate simply to say, “Gamma is the midpoint of

your color range” and leave it at that. The more accurate the discussion

of gamma becomes, the more purely mathematical it becomes. Plenty of

artists out there understand gamma intuitively and are able to work with

it without knowing the math behind it—but here it is anyway. Gamma

adjustment shifts the midpoint of a color range without affecting the

black or white points. This is done by taking a pixel value and raising

it to the inverse power of the gamma value: newPixel = pixel (1/gamma)

You’re probably used to thinking of pixel values as fitting into the range 0 to 255, but this formula works with values normalized to 1. 0 is 0, 255 is 1, and 128 is 0.5—which is how the math “normally” operates behind the scenes in computer graphics. Gamma

operates according to the magic of logarithms: Any number to the power

of 0 is 1, any number to the power of 1 is itself, and any fractional

value (less than 1) raised to a higher power approaches 0 without ever

reaching it. Lower the power closer to 0 and the value approaches 1,

again without ever reaching it. Not only that, but the values distribute

proportionally, along a curve, so the closer an initial value is to

pure black (0) or pure white (1) the less it is affected by a gamma

adjustment. |

By mixing these five

controls together, have we covered Levels? No—because there are not, in

fact, five basic controls in Levels (Input and Output White and Black

plus Gamma), but instead, five times five (RGB, Red, Green, Blue, and

Alpha).