Shooting

on film is still a valid choice. Film offers greater flexibility for

low-light situations, and it offers some aesthetic options not afforded

by digital capture. Many purists swear that shooting film adds richness

in detail and color, as well as introduces subtle nuances like film

grain, which cannot be replicated with a digital camera. Additionally,

many pictures that you’ll need to work with might only exist on

traditional media (such as prints) or as a negative. You’ll need to use a

scanner to turn these optical formats into digital formats.

Note: Other Applications

Digital

photographers who have large collections of digital images to manage

will often use a library management application. Two of the most popular

are Adobe Lightroom and Apple Aperture. Both have excellent integration

with Adobe Photoshop.

Choosing a Scanner

If you work in a computer lab or

other work environment, your choice in scanners may have already been

made for you. However, it is still important to understand the different

types of scanners that are available to consumers.

Flatbed scanners

The most common scanner type is

a flatbed scanner on which photos are loaded face down on a piece of

glass. The scanner then moves a charge-coupled device (CCD) across the

image to capture/digitize the image. High-quality scans can greatly

increase the amount of data that is captured. So, be sure to look at

high-speed scanner-to-computer connection options. For a modern

computer, FireWire or USB 2 are the best options.

Be sure to pay close

attention to the optical resolution of the scanner: This is the maximum

size of the image before using software interpolation to enlarge it.

Most users doing intermediate-level work or desktop publishing find a

scanner capable of 600 to 1200 spi to be adequate. Remember, samples per

inch can translate fairly well into pixels per inch. It is a good idea

to have more pixels to start with, and then reduce the size of the image

for delivery.

| Output Method | Typical ppi |

|---|

| Onscreen (Web/slides) | 72–96 | | Laser printing | 150–250 | | Newsprint | 120–170 | | Offset printing | 250–300 | | High-quality offset printing | 300–600 |

|

Film/slide scanners

Specialized scanners load

in slides or film negatives. These scanners use a tray to hold the

material, and then a motor pulls the tray slowly across an optical

sensor. This process is relatively slow due to the resolution needed.

The scanner must capture a lot of data from a very small surface area to

produce a usable image. These scanners are slightly more expensive than

flatbed scanners but are essential if you frequently work with slides

or negatives.

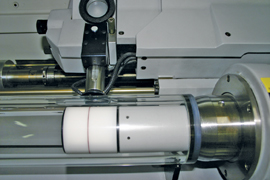

Drum scanners

When top image quality is a

must, pros turn to drum scanners. These units are very expensive

(starting at $5,000 and increase significantly). This is the oldest

scanning technology. It calls for the image to be mounted on a drum. The

drum is then rotated in front of a photomultiplier tube. The tube is

much more sensitive than the CCDs used in flatbed scanners. Drum

scanners’ primary advantage is resolution, and they should be used when

you need to significantly enlarge a scanned image (such as museum

archival pieces or for magazine output). Because the machines are

expensive and very complex (as well as potentially destructive), users

will often send images to a service bureau for drum scanning.

A

drum scanner is a highly specialized piece of equipment. These machines

are very expensive and are usually found only in high-end service

bureau facilities.

What Size to Scan? Think in Pixels

People

often get confused when determining which settings to scan with. Too

little information and the picture goes soft. Too much information and

the scanner slows to a crawl. The answer is to know your intended output

resolution as well as your device.

Tip: Need a Scanner?

Many all-in-one printers

combine a printer and scanner, essentially creating a fax machine and

photocopier in the process. Be sure to check if your printer offers

scanning software to load your traditional photos. You can also rent

scanners at many local photocopy shops.

For example, if you need to

create a 20-inch-wide poster that will be printed on a high-quality

press requiring 300 ppi, use this calculation:

20 (inches) × 300 (ppi) × 1.25 (pad for flexibility) = 7500 pixels

Do

not adjust your scanner’s dpi (or ppi) settings. Rather, crop the image

after running a preview scan. You can then adjust the scanner’s

resolution by looking at the output size of the scanned file. As you

adjust the output file size, the scanning software will automatically

determine the appropriate settings for samples per inch. All scanners

tell you just how many samples you are about to capture. Looking at

these numbers gives you a truer sense of the end result. Total pixel

count is much more important than dpi, especially when scanning images

of various original sizes.