Pictures that would have been too

expensive and impractical to commission could be picked from a catalogue. The

internet brought instant access. Royalty-free licensing made buying simple. As

digital cameras cut the cost of photography, supply increased and prices

continued to fall. Today, you can browse millions of images in a few seconds

and buy the one you need for a few pounds.

Image

libraries changed the world for designers

And this has also changed the world for

photographers. Some feel low-priced stock has devalued professional

photography. Others see it as a way to sell images on the side to buyers who

never had the budget to use photography before. Few doubt that it’s contributed

to the blurring of boundaries between amateur and pro.

In this article we’ll look at how both

buyers and sellers can get the most out of stock libraries, how their pricing

structures work, and what they now offer in addition to photos – including

illustrations, video, audio, and design work for both print and web.

FOR THE BUYER, the new generation of ‘microstock’ sites offers simplicity, low

prices and enormous choice. You can usually start searching without even

creating an account, though you’ll need to sign up to access all the features

and create your own ‘light boxes’ to keep track of the images you find.

There’s generally no obligation to provide

credit card details at this stage. When you decide to purchase an image, you

either buy a number of site ‘credits’ from which the cost of your downloads

will be deducted, or take out a subscription entitling you to download a

maximum number of images per day. When you buy images for credits, the price

will vary according to what resolution you pick, so a version suitable for A4

print will cost more than a size appropriate to a blog. On subscription plans,

you can usually download the highest resolution at no extra cost. It’s a topic

slightly too big for this articles, but do be sure that you understand how

resolution works before buying stock.

Illustrations, an increasingly popular

element of stock libraries, may be supplied as images or in some cases as

vector files, which can be placed in DTP documents or edited with software such

as Adobe Illustrator. Confusingly, some libraries use the term ‘Illustration’

as a synonym for vector-based artwork, although image files may also be

illustrations rather than photos, perhaps consisting of modified photography or

created using 3D software. Vector files generally cost more, but can be used at

any size without loss of quality.

Adobe

Illustrator software

Microstock images, and indeed most stock

images these days, are sold on a ‘royalty free’ basis. This means you pay once

for an image and you can then use it as many times as you like and in whatever

way you like, within the terms of the licence. This normally includes

everything except top-end work, such as high-circulation magazine covers or

advertising campaigns, and merchandise, such as printing onto T-shirts that

customers can order (as opposed to your or your client’s own promotional use);

an extended licence is usually available for such purposes at extra cost. One

thing that won’t be permitted under any circumstances is reselling the image

itself – logically enough, you can’t buy royalty-free stock to other buyers.

Watch out for limitations on digital distribution, too: many libraries prohibit

use above a certain size on the web, to avoid the risk of unlicensed copies

getting into circulation.

Remember that a royalty-free licence only

covers copyright, not other rights that you might potentially infringe. If

there are people visible in a picture, a model release is normally required

from each of them to use it for commercial purposes. A similar release is

required where a distinctive building or work of art features prominently in ma

photo. Most royalty-free libraries insist on these releases being provided by

the seller, but check the terms and conditions of the library you’re using.

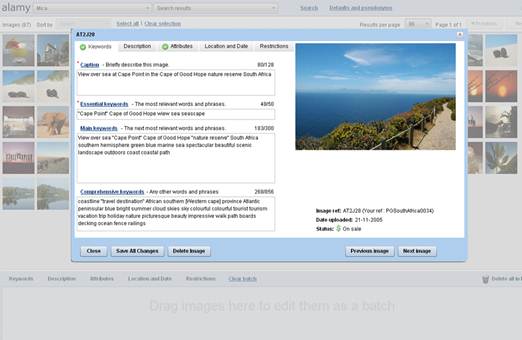

Some, such as Alamy, list separately whether releases have been obtained for

each image. Others offer a special category of ‘editorial use only’ images,

which aren’t cleared; it’s generally safe for you to use these in magazines,

newspapers and similar publications, but not as covers and not in advertising

or marketing.

Alamy,

list separately whether releases have been obtained for each image

Another reason for an image to be classed

as editorial is if it contains trademarks, such as company logos. Take care not

to use a picture containing an obvious logo – even something like the Apple

logo on a Mac - in commercial work, because your client could be sued for

trademark infringement and this will come back to you.

Model releases generally have an ‘illegal

or immoral’ clause, so think twice about using an image in a way that the

original model might reasonably object to – although, clearly, if an

image is caption ‘Posed by model’ is useful to avoid any possible

misinterpretation.

Also keep in mind that while you can use

the images you buy as many times as you like, and in work for any and all of

your clients, you’re not licensed to supply those images to clients for them to

re-use in other work. If they want to do so, they’ll need to purchase them

again from the stock library. Where costs are low, clients shouldn’t mind if

this arises, but you do need to stay on the right side of the rules; stock

libraries have no sense of humour about their content being re-used or

distributed illegally. Similarly, if you buy a subscription, it’s absolutely

prohibited (unless you pay for a multi-user account) to let other users

‘borrow’ your login and download images within your allocation.

With these caveats, buying royalty-free

stock is really very straightforward, and, as you’ll see from the examples we

feature, very affordable. Try a few different libraries and you’ll soon get a

feel for which ones have the kind of images you need – and, just as

importantly, which search engines feel quick and intuitive. All of this is to a

great degree a matter of personal taste.

Don’t be surprised to see the same images

crop up on multiple sites. Sellers have the choice of whether to stay exclusive

to one library or not, and many don’t, preferring to hedge their bets. The

images that are exclusive will tend to be the most distinctive – and in many

cases a little more expensive.