Transform controls live under every layer’s twirly

arrow. There are keyboard shortcuts to each Transform property. For a

standard 2D layer these are

A for Anchor Point, the center pivot of the layer

P for Position, by default the center of the composition

S for Scale (in percent of source)

R for Rotation (in revolutions and degrees)

T

for Opacity, or if it helps, “opaci-T” (which is not technically

spatial transform data but is grouped here anyhow because it’s

essential)

Once you’ve revealed one of these, hold down the Shift

key to toggle another (or to hide another one already displayed). This

keeps only what you need in front of you. A 3D layer reveals four

individual properties under Rotation to allow full animation on all

axes.

Add the Alt (Opt)

to each of these one-letter shortcuts to add the first keyframe; once

there’s one keyframe, any adjustments to that property at any other

frame generate another keyframe automatically.

There are selection tools to correspond to perform Transform adjustments directly in the viewer:

V activates the Selection tool, which also moves and scales in a view panel.

Y switches to the Pan-Behind tool, which moves the anchor point.

W is for “wotate”—it adjusts Rotation. Quite the sense of humor on that After Effects team.

Once you adjust with any of

these tools, an Add Keyframe option for the corresponding property

appears under the Animation menu, so you can set the first keyframe

without touching the Timeline panel at all.

Graph Editor

The project

02_bouncing_ball.aep in the accompanying disc’s examples folder contains

a simple animation, bouncing ball 2d, which can be created from

scratch; you can also see the steps below as individual numbered compositions.

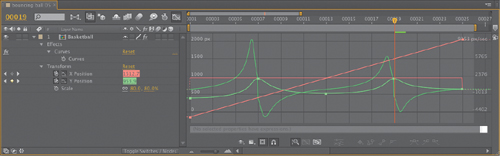

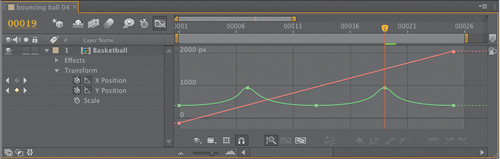

To enable the Graph Editor, click its icon in the Timeline panel  or use the shortcut Shift+F3. Below the grid that appears in place of the layer stack are the Graph Editor controls (Figure 1).

or use the shortcut Shift+F3. Below the grid that appears in place of the layer stack are the Graph Editor controls (Figure 1).

Show Properties

By default, if nothing is

selected, nothing displays in the graph; what you see depends on the

settings in the Show Properties menu  . Three toggles in this menu control how animation curves are displayed in the graph:

. Three toggles in this menu control how animation curves are displayed in the graph:

Tip

To work in the Graph Editor without worrying about what is selected, disable Show Selected Properties and enable the other two. |

Show Selected Properties displays whatever animation property names are highlighted.

Show Animated Properties shows everything with keyframes or expressions.

Show Graph Editor Set displays properties with the Graph Editor Set toggle enabled.

Show Selected Properties is the

easiest to use, but Show Graph Editor Set gives you the greatest

control. You decide which curves need to appear, activate their Graph

Editor Set toggle, and after that it no longer matters whether you keep

them selected.

Tip

The

other recommended change prior to working through this section is to

enable Default Spatial Interpolation to Linear in Preferences >

General (Ctrl+Alt+; or Cmd+Opt+;). Try this if your initial animation doesn’t seem to match that shown in Figure 3.

|

To begin the bouncing ball animation, include Position in the Graph Editor Set by toggling its icon  . Alt+P (Opt+P) sets the first Position keyframe at frame 0; after that, any changes to Position are automatically keyframed.

. Alt+P (Opt+P) sets the first Position keyframe at frame 0; after that, any changes to Position are automatically keyframed.

Basic Animation and the Graph View

Figure 2

shows the first step: a very basic animation blocked in using Linear

keyframes, evenly spaced. It won’t look like a bouncing ball yet, but

it’s a typical way to start when animating, for new and experienced

animators alike.

To get to this point, do the following:

Having set the first keyframe at frame 0, move the ball off the left of the frame.

At frame 24, move the ball off the right of the frame, creating a second keyframe.

Create a keyframe at frame 12 (just check the box, don’t change any settings).

Now add the bounces: At frames 6 and 18 move the ball straight downward so it touches the bottom of the frame.

This leaves five Position

keyframes and an extremely unconvincing-looking bouncing ball

animation. Great—it always helps to get something blocked in so you can

clearly see what’s wrong. Also, the default Graph Editor view at this

point is not very helpful, because it displays the speed graph, and the

speed of the layer is completely steady at this point—deliberately so,

in fact.

To get the view shown in Figure 2, make sure Show Reference Graph is enabled in the Graph Options menu  . This is a toggle even advanced users miss, although it is

now on by default. In addition to the not-very-helpful speed graph you

now see the value graph in its X (red) and Y (green) values. However,

the green values appear upside-down! This is the flipped After Effects Y

axis in action; 0 is at the top of frame so that 0,0 is in the top-left

corner, as it has been since After Effects 1.0, long before 3D

animation was even contemplated.

. This is a toggle even advanced users miss, although it is

now on by default. In addition to the not-very-helpful speed graph you

now see the value graph in its X (red) and Y (green) values. However,

the green values appear upside-down! This is the flipped After Effects Y

axis in action; 0 is at the top of frame so that 0,0 is in the top-left

corner, as it has been since After Effects 1.0, long before 3D

animation was even contemplated.

Notes

Auto Select Graph Type selects speed graphs for spatial properties and value graphs for all others. |

Ease Curves

The simplest way to “fix” an

animation that looks too stiff like this is often to add eases. For this

purpose After Effects offers the automated Easy Ease functions,

although you can also create or adjust eases by hand in the Graph

Editor.

Warning

Mac

users beware: The F9 key is used by the system for the Exposé feature,

revealing all open panels in all applications. You can change or disable

this feature in System Preferences > Dashboard & Exposé. |

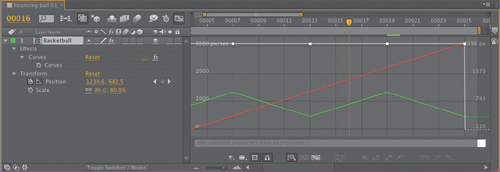

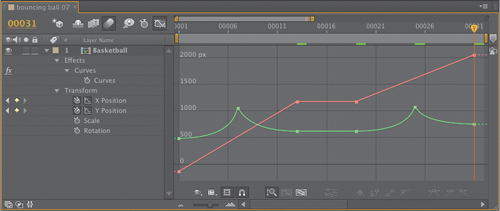

Select all of the “up” keyframes—the first, third, and fifth—and click Easy Ease  (F9).

When a ball bounces, it slows at the top of each arc, and Easy Ease

adds that arc to the pace; what was a flat-line speed graph now is a

series of arcing curves (Figure 3).

(F9).

When a ball bounces, it slows at the top of each arc, and Easy Ease

adds that arc to the pace; what was a flat-line speed graph now is a

series of arcing curves (Figure 3).

Technically, you could have applied Easy Ease Out  (Ctrl+Shift+F9/Cmd+Shift+F9) to the first keyframe and Easy Ease In

(Ctrl+Shift+F9/Cmd+Shift+F9) to the first keyframe and Easy Ease In  (Shift+F9)

to the final one, because the ease in each case only goes in one

direction. The “in” and “out” versions of Easy Ease are specifically for

cases where there are other adjacent keyframes and the ease should only

go in one direction (you’ll see one in a moment). In this case it’s not

really necessary.

(Shift+F9)

to the final one, because the ease in each case only goes in one

direction. The “in” and “out” versions of Easy Ease are specifically for

cases where there are other adjacent keyframes and the ease should only

go in one direction (you’ll see one in a moment). In this case it’s not

really necessary.

Meanwhile, there’s a clear

problem here: The timing of the motion arcs, but not the motion itself,

is still completely linear. Fix this in the Composition viewer by

pulling Bezier handles out of each of the keyframes you just eased:

1. | Deselect all keyframes but leave the layer selected.

|

2. | Make sure the animation path is displayed (Ctrl+Shift+H/Cmd+Shift+H toggles).

|

3. | Click on the first keyframe in the Composition viewer to select it; it should change from hollow to solid in appearance.

|

4. | Switch to the Pen tool with the G

key; in the Composition viewer, drag from the highlighted keyframe to

the right, creating a horizontal Bezier handle. Stop before crossing the

second keyframe.

|

5. | Do the same for the third and fifth keyframes (dragging left for the fifth).

|

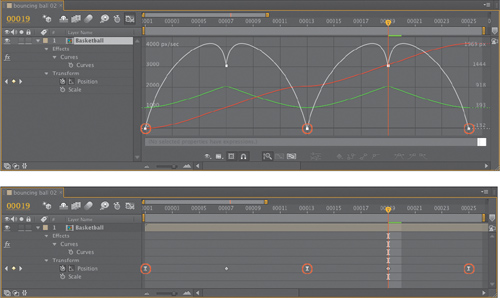

The animation path now looks more like you’d expect a ball to bounce (Figure 4).

Preview the animation, however, and you’ll notice that the ball crudely

pogos across the frame instead of bouncing naturally. Why is that?

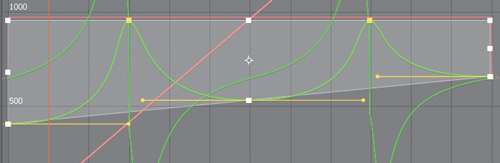

Separate XYZ

The Graph Editor reveals

the problem. The red X graph shows an unsteady horizontal motion due to

the eases. The problem is that the eases should be applied only to the

vertical Y dimension, whereas the X animation travels at a constant

rate.

New to After Effects CS4 was

the ability to animate X and Y (or, in 3D, X, Y, and Z) animation

curves separately. This allows you to add keyframes for one dimension

only at a given point in time, or to add keyframes in one dimension at a

time.

Select Position and click Separate Dimensions  . Where there was a single Position property, there are now two marked X Position and Y Position. Now try the following:

. Where there was a single Position property, there are now two marked X Position and Y Position. Now try the following:

1. | Disable the Graph Editor Set toggle for Y Position so that only the red X Position graph is displayed.

|

2. | Select the middle three X Position keyframes—you can draw a selection box around them—and delete them.

|

3. | Select the two remaining X keyframes and click the Convert Selected Keyframes to Linear button  . .

|

Now take a look in the

Composition viewer—the motion is back to linear, although the temporal

eases remain on the Y axis. Not only that, but you cannot redraw them as

you did before; enabling Separate Dimensions removes this ability.

Instead, you can create them in the Graph Editor itself.

1. | Enable the Graph Editor Set toggle for Y Position, so both dimensions are once again displayed.

|

2. | Select

the middle Y Position keyframe, and you’ll notice two small handles

protruding to its left and right. Drag each of these out, holding the

Shift key if necessary to keep them flat, and notice the corresponding

change in the Composition viewer (Figure 5).

Tip Show Graph Tool Tips displays values of whatever curve is under the mouse at that exact point in time. |

|

3. | Select

the first and last Y Position keyframes and click Easy Ease; the

handles move outward from each keyframe without affecting the X Position

keyframes.

|

4. | Drag

the handles of the first and last Y Position keyframes as far as they

will go (right up to the succeeding and preceding keyframes,

respectively).

|

Tip

Separate

Dimensions does not play nicely with eases and cannot easily be

round-tripped back, so unfortunately you’re best to reserve it for

occasions when you really need it. |

Preview the result and

you’ll see that you now have the beginnings of an actual bouncing ball

animation; it’s just a little bit too regular and even, so from here you

give it your own organic touch.

Transform Box

The transform box lets you

edit keyframe values in all kinds of tricky or even wacky ways. Toggle

on Show Transform Box and select more than one keyframe, and a white box

with vertices surrounds the selected frames. Drag the handle at the

right side to the left or right to change overall timing; the keyframes

remain proportionally arranged.

Notes

There is a whole menu  of options to show items that you might think are only in Layer view:

layer In/Out points, audio waveforms, layer markers, and expressions.

of options to show items that you might think are only in Layer view:

layer In/Out points, audio waveforms, layer markers, and expressions. |

So, does the transform box help in this case? Well, it could, if you needed to

scale the animation timing around a particular keyframe: Drag the anchor to that frame, then Ctrl-drag (Cmd-drag)

reverse the animation: Ctrl-drag/Cmd-drag

from one edge of the box to the other (or for a straight reversal,

simply context-click and choose Keyframe Assistant > Time-Reverse

Keyframes)

Notes

The Snap button  snaps to virtually every visible marker, but not—snap!—to whole frame values if Allow Keyframes Between Frames is on snaps to virtually every visible marker, but not—snap!—to whole frame values if Allow Keyframes Between Frames is on  . . |

diminish the bounce animation so that the ball bounces lower each time: Alt-drag (Opt-drag) on the lower-right corner handle (Figure 6)

If you Ctrl+Alt-drag (Cmd+Opt-drag) on a corner that will taper values at one end, and if you Ctrl+Alt+ Shift-drag (Cmd+Opt+Shift-drag)

on a corner, it will skew that end of the box up or down. I don’t do

that kind of stuff much, but with a lot of keyframes to scale

proportionally, it’s a good one to keep in your back pocket.

Holds

At this point you may have a

fairly realistic-looking bouncing ball; maybe you added a little

Rotation animation so the ball spins forward as it bounces, or maybe

you’ve hand-adjusted the timing or position keys to give them that extra

little organic unevenness. Hold keyframes won’t help improve this

animation, but you could use them to go all Matrix-like with it, stopping the ball mid-arc before continuing the action. A Hold keyframe  (Ctrl+Alt+H/Cmd+Shift+H) prevents any change to a value until the next keyframe.

(Ctrl+Alt+H/Cmd+Shift+H) prevents any change to a value until the next keyframe.

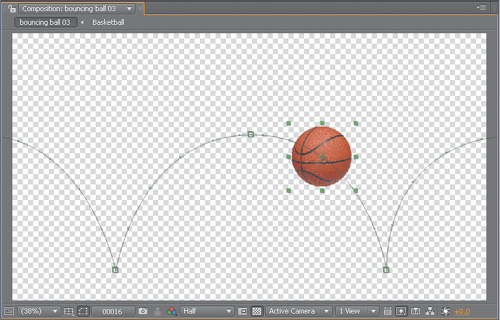

Drag all keyframes from the one

at the top of the middle arc forward in time a second or two. Copy and

paste that mid-arc keyframe (adding one for any other animated

properties or dimensions at that point in time) back to the original

keyframe location, and toggle it to a Hold keyframe (Figure 7).

Beyond Bouncing Balls

In

the (reasonably likely) case that the need for a bouncing ball

animation never comes up, what does this example show you? Let’s recap:

You can control a Bezier motion path in the Composition viewer using the Pen tool.

Realistic

motion often requires that you shape the motion path Beziers and add

temporal eases; the two actions are performed independently on any given

keyframe, and in two different places (in the viewer and Timeline

panel).

Animation can get a little trickier in 3D, but the same basic rules apply .

Three preset keyframe transition types are available, each with a shortcut at the bottom of the Graph Editor: Hold  , Linear

, Linear  , and Auto Bezier

, and Auto Bezier  . Adjust the handles or apply Easy Ease and the preset becomes a custom Bezier shape.

. Adjust the handles or apply Easy Ease and the preset becomes a custom Bezier shape.

Copy and Paste Animations

Yes, copy and paste; everyone

knows how to do it. Here are some things that aren’t necessarily

obvious about copying and pasting keyframe data:

Copy a set of

keyframes from After Effects and paste them into an Excel spreadsheet or

even an ordinary text editor, and behold the After Effects keyframe

format, ready for hacking.

You

can paste from one property to another, so long as the format matches

(the units and number of parameters). Copy the source, highlight the

target, and paste.

Tip

You can

use an Excel spreadsheet to reformat underlying keyframe data from other

applications; just paste in After Effects data to see how it’s

formatted, and then massage the other data to match that format (if you

have Excel skills, so much the better). Once done, copy and paste the

data back into After Effects. |

Keyframes

respect the position of the current time indicator; the first frame is

always pasted at the current time (useful for relocating timing, but

occasionally an unpleasant surprise).

There’s a lock on the Effect Controls tab to keep a panel forward even when you select another layer to paste to it.

Copy and paste keyframes from an effect that isn’t applied to the target, and that effect is added along with its keyframes.

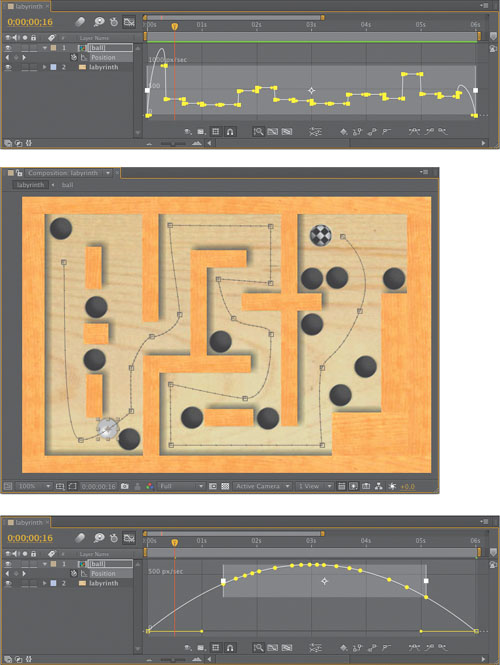

Close-up: Roving Keyframes

Sometimes

an animation must follow an exact path, hitting precise points, but

progress steadily, with no variation in the rate of travel. This is the

situation for which Roving keyframes were devised. Figure 8

shows a before-and-after view of a Roving keyframe; the path of the

animation is identical, but the keyframes proceed at a steady rate.

|

Pay close attention to the current time and what is selected when copying, in particular, and when pasting animation data.

Layer vs. Graph

To summarize the distinction between layer bar mode and the Graph Editor, with layers you can

block in keyframes with respect to the overall composition

establish broad timing (where Linear, Easy Ease, and Auto-Bezier keyframes are sufficient)

The Graph Editor is essential to

refine an individual animation curve

compare spatial and temporal data

scale animation data, especially around a specific pivot point

perform extremely specific timing (adding a keyframe in between frames, hitting a specific tween point with an ease curve)

In either view you can

edit expressions

change keyframe type (Linear, Hold, Ease In, and so on)

make

editorial and compositing decisions regarding layers such as

start/stop/duration, split layers, order (possible in both views, easier

in Layer view)

By no means, then, does the

Graph Editor make Layer view obsolete; Layer view is still where the

majority of compositing and simple animation is accomplished.

Notes

You

must enable Allow Keyframes Between Frames in the Graph Editor or they

all snap to exact frame increments. However, when you scale a set of

keyframes using the transform box, keyframes will often fall in between

frames whether or not this option is enabled. |