From a usability point of

view, the navigation and layout of your mobile site are of great

importance. But turn your attention to the content that the site exists

to display and present. In this section, you look at the "body" of the

site's pages, for want of a better word, and the material and

information that users are on your site to see.

1. Text and Typography

Even if your site is, say, a dedicated photo gallery,

many parts of it need to display textual content. Your goal, obviously,

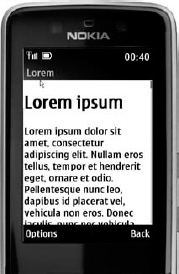

is to make this as readable and accessible as possible. Many older or

less-capable mobile handsets do not encourage lots of variation in how

textual content is displayed. Until quite recently, mobile devices had

little concept of font families, and the web browsers displayed text in

the native system font of the operating system — often at one fixed

size, regardless of how the web developer wanted it to be styled. Figure 1

shows a Nokia Series 40 browser, displaying the platform's default font

family, despite each line of the web page being styled with different {font-family:} CSS rules.

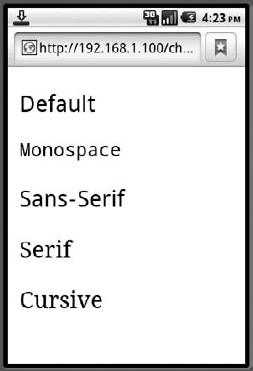

Other WebKit-based browsers do better, but are still

inconsistent: Apple iPhone and Android devices do at least have multiple

fonts, but default differently (serif for the former, sans-serif for

the latter), as shown in Figures 2 and 3. Some variability also results when using {font-size:} and {font-weight:} rules on different devices.

Although you can invest effort in styling fonts

differently for different devices, and perhaps trying to reduce the

point size of text for links in headers and footers and so on, there's a

good argument for just leaving the body text's font, weight, size, and

line-spacing alone and letting the device render it with native

defaults. At least you can expect some consistency with the rest of the

device's operating system, and you can be sure that the font will be

legible. You certainly cannot assume pixel-level control over font

display on all mobile devices.

For sites that absolutely require specific typography, it is worth considering the usage of CSS3 @font-face,

which allows you to package suitably-licensed font files that the

browser can use in addition to its native fonts. This is currently

supported on a very limited number of devices and often requires the

right format of font file. Apple's iPhone only supports font-face with

SVG-format fonts, for example. However, you are bound to see increasing

support for font-face across other types of devices in the years to

come.

2. Pagination

Page size is a perennial consideration for mobile web

developers. Historically, there were actually hard limits on the (byte)

size of page that many devices could display and cache, and slower

network speeds meant that large pages might simply take too long to

load.

On more contemporary mobile devices, the memory

capacity of the browser is no longer an absolute limit, and faster

mobile networks mean that large portions of text are relatively quick to

download. But large page size is still a consideration from a usability

point of view. Remember that the physical screen is much smaller and

the user can view far less text without having to scroll.

About five paragraphs, 800 words, or 5,000 bytes of

default-styled text (on a web page with fluid width) will fill an

average laptop screen. The same text on an Apple iPhone, for example,

will fill five full pages in portrait mode, or about nine pages in

landscape mode (due to the way the iPhone rescales fonts by default for

the two orientations). This requires the user to make at least that

number of scrolling flicks to read the same text.

For a large smart phone device, this is tolerable,

and the smooth, continuous nature of touch-screen panning makes the act

of scroll-as-I-read almost a subconscious one to the user. On a

non-touch screen device — even with a good browser — the impact is far

higher though. On the Nokia Series 40 browser shown in Figure 6-27,

for example, the same text occupies 15 screens of 12 lines each. If

each click moves the scroll bar down a few lines at a time, the user is

required to do lots of downward cursor movement simply to view the whole

article. And on some older handsets, the mere act of patiently

scrolling a sluggish browser down through a large page can become an

ordeal in itself.

For this reason, many sites add aggressive pagination

for long articles of text, breaking them up into bite-sized pieces that

both the user and the device can consume efficiently. In theory, this

doesn't reduce the time taken to read through a large article — in fact,

it may increase it — but it does make the user interface more

responsive, and it allows the user to "snack" on the content rather than

download the whole thing and scroll painstakingly down through it.

The good news about pagination is that most CMS

support it natively or with plug-ins, and the platform should be able to

slice up articles and content automatically, placing "next" and

"previous" or "page M of N" links at the bottom of each page, while

being smart enough not to break pages in the middle of sentences,

paragraphs, tables, or lists. The bad news is that to do it properly for

mobile, the pagination algorithm should ideally be parameterized by

knowledge about the device requesting the page: For a smart touch-screen

handset with a small font, the pages can be larger and fewer; for an

older handset with a limited memory, they should be smaller and more

numerous.

With regard to URLs for pagination, the most

reasonable solution is to use the query string to indicate ordinality:

/article-1?page=2, article-1?page=3, and so on. If you are slicing the

article in different places according to the device, the page number in

the query string might be offset slightly if users share deep paginated

links between different browsers — but this is hardly a major issue and

at least the base part of the URL can be guaranteed to take the user to

the top of the article.