1. Monitoring

Historically, Exchange monitoring was performed

via an external monitoring solution such as System Center Operations

Manager (SCOM) or SolarWinds. These types of applications gather

information from the service such as performance data, event logs, mail

delivery metrics, and so on. Then they store that data in a database

for analysis. Following that, the monitoring solution takes action

based on the recorded data. For example, SCOM has a collection of

Health Manifests that can trigger when a service is not running or if a

performance counter is outside acceptable thresholds.

The problem with these types of

applications is that they require fine-tuning for most deployments.

Even for the Exchange Online part of Office 365, the SCOM deployment

requires heavy customization to meet the operating requirements.

The root cause of this monitoring problem

is simple. Albert Einstein said it the best: “Not everything that can

be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” What

this means is that just because we can alert on how many milliseconds

an operation took to complete, it doesn't necessarily mean that we

should. Likewise, what is important is how the system is perceived to

be meeting the demands of its end users. Recording how long an I/O

operation took to complete is simple. Likewise, it's simple to define

some thresholds and take action if they are exceeded. However, what if

the threshold was exceeded and the end-user experience was just fine?

How can we monitor the experience provided to the customers of our

messaging service?

The truth is that a quality monitoring

solution will require as much effort to design as the underlying

service that it is monitoring. Not only will it monitor easy-to-harvest

system data from event logs, performance counters, and message tracking

logs, but it will also simulate user requests from outside the

organization to observe how the system is performing from a user

perspective. The solution should also be able to take action to fix

common scenarios, such as failing over workload from an unhealthy DAG

node to a healthy alternative.

2. Alerting

Alerting is what a monitoring solution

does when something unusual has occurred. Historically, monitoring

solutions ship with a database of thresholds for events and performance

counters that, if exceeded, will result in some form of notification

being dispatched: a Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) trap or

an email, an SMS message, or a combination of both. The expectation is

that a human being will eventually be tasked with resolving whatever

anomaly is present.

As IT systems have evolved and have become

ever more complex, so too have the systems designed to monitor and

produce alerts on them. The bottom line is that it is a waste of time

and effort to page an expensive on-call resource to fix something that

is not directly affecting service. More significantly, the risk of

human error increases dramatically when complex infrastructure is

resolved under pressure by on-call resources.

One way to approach the issue of when to

contact such resources is to consider service impact as a part of the

alert. This can be complicated, however, and so it generally will

require human involvement. (For example, it may not be an Exchange

problem that has taken down service.) As a general rule, there are

three types of failure in an Exchange 2013 system:

- Non-service-affecting failure

- Service-affecting failure

- Data corruption event

In the case of a non-service-affecting failure,

the resolution will vary depending on what exactly has failed. If you

have a DAG and other high-availability features, a single server

failure or storage chassis failure could fall into in this category. If

you have four copies of the data spread across four DAG nodes and one

node fails, you still have three left, and so there is no real

requirement to summon on-call resources. Instead, the failure should be

investigated and resolved by the normal operations teams during normal

working hours.

Service-affecting failures are

significant in that there are end users without service. This is a no

brainer—on-call resources should be mobilized, but “who you gonna

call?” as the trio from Ghostbusters would say. Some of the

worst cases we have worked on with Exchange systems had their root

cause in a disaster recovery event where resolution was first attempted

by the wrong resource and hence was done incorrectly. The single most

important aspect of a service-affecting failure is to get the right

resource to the right place as quickly as possible. It also helps if

there is a set of predetermined scenarios readily available to resolve

predictable problems, such as database reseeds or DAG node rebuilds.

Data corruption events are

the worst type of alert, and they should be treated with the highest

priority (so-called red alerts). There are various kinds of potential

data corruption within Exchange, and all should be treated immediately.

However, by far the worst is something called a lost flush. A lost flush

occurs when Exchange thinks it has written data to the disk, but that

data never got there—despite the operating system receiving

confirmation that it did. Exchange attempts to detect these issues, and

it will raise an alert if it detects one. Our guidance is to treat data

corruption events with the highest possible priority—even if they are

not affecting service. Have a remediation plan for data corruption and

make sure that your team is drilled in its use. If a lost flush is

detected, remove the suspect storage hardware from service

immediately—do not put it back into production until the root cause is

identified and resolved.

3. Inventory

Maintaining a list of hardware and software

components that make up your Exchange service is extremely useful.

Patching and maintaining an Exchange service can be complex, especially

at scale. In the past, we have seen organizations that believed that all

of their Exchange Servers were at a specific patch level, only to

discover that some were not when we verified them physically. This

problem only gets worse once you begin to include operating system

patches, hardware drivers, and, potentially, even things such as

hardware load balancer operating systems. All of these things can

impact the service and the way the components interact with each other.

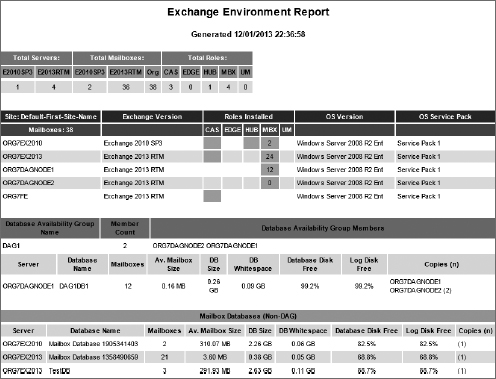

Figure 1

shows a sample output of this script. The script provides most of the

critical information that an Exchange team will require to operate

their service successfully.

FIGURE 1 Example Exchange Environment Report

We recommend keeping track of the following core information about your Exchange platform:

Organization information

- Organization name

- Versions of Exchange installed

- Number of servers installed

- Number of mailboxes in total

- Ad-site topology

Per-server information

- Operating system

- Exchange roles installed

- Exchange version and patches

- Mailbox databases per server

- Network card device driver and firmware

- Host bus adapter/RAID controller device driver and firmware

- Version of storport installed

- Build date

DAG and database information

- Database availability groups

- Database availability group membership

- Number of mailboxes per database

- Mailboxes in each database availability group

- Database/log LUN capacity usage

The free script provides an amazing

starting point for this information. It does not gather everything, but

what it does gather is useful and easy to generate. It also shows what

is possible natively with PowerShell.

For many enterprise organizations, a free

script will not meet their requirements adequately. Connecting to their

corporate inventory system may be a part of the production handover

process, but it may still be useful for the Exchange operations teams

to maintain their own specific data about their service, since it will

be more readily available and easier to modify if additional

information is required. It is not unusual to see multiple inventory

systems in use in large enterprises due to different teams requiring

different information. For example, IT leadership may be interested in

server numbers, costs, and licensing but probably not the device driver

for the RAID controller in use on mailbox servers.

Our recommendation is to give

Steve's free PowerShell script a test run, modify and update it as

appropriate, and schedule it to update the HTML daily.