Suppose someone told you that you stand 19

units tall. What do you conclude from that information? Does that mean

you’re tall? short? of average height? What percent of the population

is taller than you are?

You don’t know, and you can’t know, because you

don’t know how long a “unit” is. If a unit is four inches long, then

you stand 76 inches, or 6′4″ (rather tall). If a unit is three inches

long, then you stand 57 inches, or 4′9″ (rather short).

The problem is that there’s nothing standard about the word unit.

(In fact, that’s one of the reasons it’s such a useful word.) Now

suppose further that the mean height of all humans is 20 units. If

you’re 19 units tall, you know that you’re shorter than average.

But how much shorter is one unit shorter? If, say,

3% of the population stands between 19 and 20 units, then you’re only a

little shorter than average. Only 3% of the population stands between

you and the average height.

If, instead, 34% of the population were between 19

and 20 units tall, then you’d be fairly short: Everyone who’s taller

than the mean of 20, plus another 34% between 19 and 20 units, would be

taller than you.

Suppose now that you know

the mean height in the population is 20 units, and that 3% of the

population is between 19 and 20 units tall. With that knowledge, with

the context provided by knowing the mean height and the variability of

height, “unit” becomes a standard. Now when someone tells you that

you’re 19 units tall, you can apply your knowledge of the way that

standard behaves, and immediately conclude that you’re a skosh shorter

than average.

Arranging for a Standard

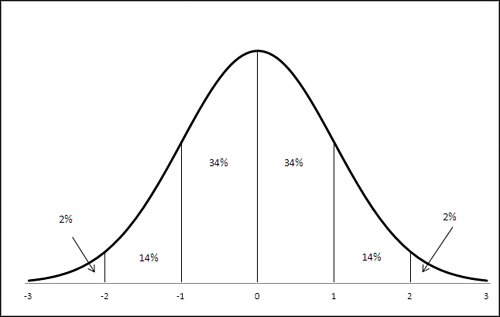

A standard deviation acts much like the fictitious unit described in the prior section. In any frequency distribution that follows a normal curve, these statements are true:

You find about 34% of the records between the mean and one standard deviation from the mean.

You find about 14% of the records between one and two standard deviations from the mean.

You find about 2% of the records between two and three standard deviations from the mean.

These standards are displayed in Figure 1.

The numbers shown on the horizontal axis in Figure are called z-scores.

A z-score, or sometimes z-value, tells you how many standard deviations

above or below the mean a record is. If someone tells you that your

height in z-score units is +1.0, it’s the same as saying that your

height is one standard deviation above the mean height.

Similarly, if your weight in z-scores is −2.0, your weight is two standard deviations below the mean weight.

Because of the way that z-scores slice up the

frequency distribution, you know that a z-score of +1.0 means that 84%

of the records lie below it: Your height of 1.0 z means that you are as

tall as or taller than 84% of the other observations. That 84%

comprises the 50% below the mean, plus the 34% between the mean and one

standard deviation above the mean. Your weight, −2.0 z, means that you

outweigh only 2% of the other observations. Hence the term standard deviation. It’s standard

because it doesn’t matter whether you’re talking about height, weight,

IQ, or the diameter of machined piston rings. If it’s a variable that’s

normally distributed, then one standard deviation above the mean is

equal to or greater than 84% of the other observations. Two standard

deviations below the mean is equal to or less than 98% of the other

observations.

It’s a deviation

because it expresses a distance from the mean: a departure from the

mean value. More on that shortly, in

“Dividing by N − 1,” but first it’s helpful to bring in a little more

background.

Thinking in Terms of Standard Deviations

With some important exceptions, you are likely to

find yourself thinking more about standard deviations than about other

measures of variability. The standard deviation is in

the same unit of measurement as the variable you’re interested in. If

you’re studying the distribution of miles per gallon of gasoline in a

sample of cars, you might find that the standard deviation is four

miles per gallon. The mean mileage of car brand A might be four mpg, or

one standard deviation, greater than brand B’s mean mileage.

That’s very convenient and it’s one reason that

standard deviations are so useful. It’s helpful to be able to think to

yourself, “The mean height is 69 inches. The standard deviation is 3

inches.” The two statistics are in the same metric.

For example, it’s easy to get comfortable with

statements such as “the mean was 20 miles per gallon and the standard

deviation was 5 miles per gallon.” It’s a lot harder to feel

comfortable with “the mean was 20 miles per gallon and the variance was

25 squared miles per gallon.” What does a “squared mile per gallon”

even mean?

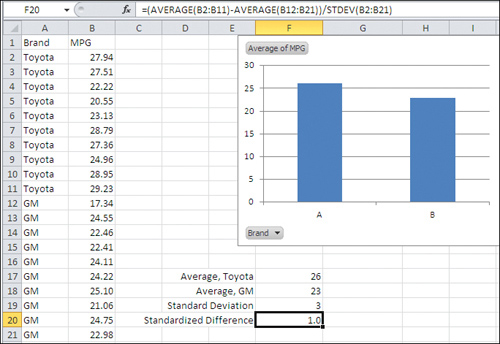

Fortunately, standard deviations are more

intuitively informative. Suppose you have the mpg of ten Toyota cars in

B2:B11, and the mpg of ten GM cars in B12:B21. One way to express the

difference between the two brands’ mean gas mileage is this:

=(AVERAGE(B2:B11) − AVERAGE(B12:B21)) / STDEV(B2:B21)

That Excel formula gets the difference in the mean

values for the two brands, and divides by the standard deviation of the

mpg for all 20 cars. It’s shown in Figure 2.

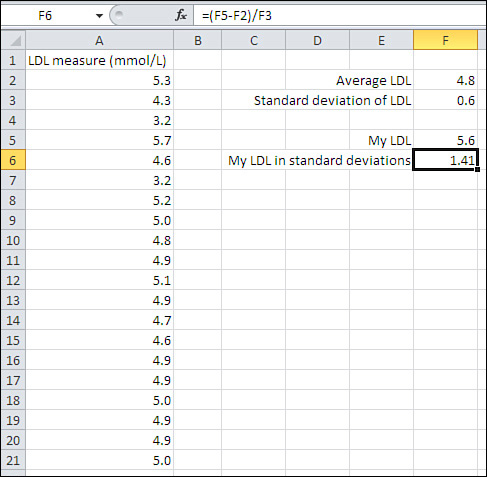

In Figure 3,

the difference between the two brands in standard deviation units is

1.0. As you become more familiar and comfortable with standard

deviations, you will find yourself automatically thinking things such

as, “One standard deviation—that’s quite a bit.” Expressed in this way,

you don’t need to know whether 26 mpg vs. 23 mpg is a large difference

or a small one. Nor do you need to know whether 5.6 mmol/L (millimoles

per liter) of LDL cholesterol is high, low, or typical.

All you need to know is that 5.6 is more than one standard deviation

above the mean of 4.8 to conclude that it indicates moderate risk of

diseases associated with the thickening of arterial walls.

The

point is that when you’re thinking in terms of standard deviation units

in an approximately normal distribution, you automatically know where a

z-score is in the overall distribution. You know how far it is from

another z-score. You know whether the difference between two means,

expressed as z-scores, is large or small.

First, though, you have to calculate the

standard deviation. Excel makes that very easy. There was a time when

college students sat side by side at desks in laboratory basements,

cranking out sums of squares on Burroughs adding machines with hand

cranks. Now all that’s needed is to enter something like =STDEV(A2:A21).