Compound effects

Sometimes we have a need

to toggle the visibility of elements, rather than displaying them once

as we did in the previous example. Toggling can be achieved by first

checking the visibility of the matched elements and then attaching the

appropriate method. Using the fade effects again, we can modify the

example script to look like this:

$(document).ready(function() {

var $firstPara = $('p:eq(1)');

$firstPara.hide();

$('a.more').click(function() {

if ($firstPara.is(':hidden')) {

$firstPara.fadeIn('slow');

$(this).text('read less');

} else {

$firstPara.fadeOut('slow');

$(this).text('read more');

}

return false;

});

});

Using an if else statement is a perfectly reasonable way to toggle elements' visibility. But with jQuery's compound effects we can leave the conditionals out of it (although, in this example, we still need one for the link text). jQuery provides a .toggle() method, which acts like .show() and .hide(), and like them, can be used with a speed argument or without. The other compound method is .slideToggle(),

which shows or hides elements by gradually increasing or decreasing

their height. Here is what the script looks like when we use the .slideToggle() method:

$(document).ready(function() {

var $firstPara = $('p:eq(1)');

$firstPara.hide();

$('a.more').click(function() {

$firstPara.slideToggle('slow');

var $link = $(this);

if ( $link.text() == "read more" ) {

$link.text('read less');

} else {

$link.text('read more');

}

return false;

});

});

This time $(this) would have been repeated, so we're storing it in the $link

variable for performance and readability. Also, the conditional

statement checks for the text of the link rather than the visibility of

the second paragraph, since we're only using it to change the text.

Creating custom animations

In addition to the pre-built effect methods, jQuery provides a powerful .animate() method that allows us to create our own custom animations with fine-grained control. The .animate() method comes in two forms. The first takes up to four arguments:

1. A map of style properties and values—similar to the .css() map

2. An optional speed—which can be one of the preset strings or a number of milliseconds

3. An optional easing type—an

4. An optional callback function—

All together, the four arguments look like this:

.animate({property1: 'value1', property2: 'value2'},

speed, easing, function() {

alert('The animation is finished.');

}

);

The second form takes two arguments, a map of properties and a map of options.

.animate({properties}, {options})

In effect, the second

argument wraps up the second through fourth arguments of the first form

into another map, and adds two more options to the mix. When we adjust

the line breaks for readability, the second form looks like this:

.animate({

property1: 'value1',

property2: 'value2'

}, {

duration: 'value',

easing: 'value',

complete: function() {

alert('The animation is finished.');

},

queue: boolean,

step: callback

});

For now we'll use the first form of the .animate() method, but we'll return to the second form later in the chapter when we discuss queuing effects.

Toggling the fade

When we discussed compound effects, did you notice that not all methods

have a corresponding method for toggling? That's right: while the

sliding methods include .slideToggle(), there is no corresponding .fadeToggle() to go along with .fadeIn() and .fadeOut()! The good news is that we can use the .animate() method to easily make our own toggling fade animation. Here, we'll replace the .slideToggle() line of the previous example with our custom animation:

$(document).ready(function() {

custom animations, creatingfadeIn() method$('p:eq(1)').hide();

$('a.more').click(function() {

$('p:eq(1)').animate({opacity: 'toggle'}, 'slow');

var $link = $(this);

if ( $link.text() == "read more" ) {

$link.text('read less');

} else {

$link.text('read more');

}

return false;

});

});

As the example illustrates, the .animate() method provides convenient shorthand values for CSS properties —'show', 'hide', and'toggle'— to ease the way when the shorthand methods aren't quite right for the particular task.

Animating multiple properties

With the .animate()

method, we can modify any combination of properties simultaneously. For

example, to create a simultaneous sliding and fading effect when

toggling the second paragraph, we simply add the height property-value pair to .animate()'s properties map:

$(document).ready(function() {

$('p:eq(1)').hide();

$('a.more').click(function() {

$('p:eq(1)').animate({

opacity: 'toggle',

height: 'toggle'

},

'slow');

var $link = $(this);

if ( $link.text() == "read more" ) {

$link.text('read less');

} else {

$link.text('read more');

}

return false;

});

});

Additionally, we have

not only the style properties used for the shorthand effect methods at

our disposal, but also other properties such as: left, top, fontSize, margin, padding, and borderWidth.

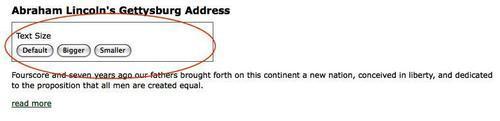

Recall the script to change the text size of the speech paragraphs. We

can animate the increase or decrease in size by simply substituting the .animate() method for the .css() method:

$(document).ready(function() {

var $speech = $('div.speech');

var defaultSize = $speech.css('fontSize');

$('#switcher button').click(function() {

var num = parseFloat( $speech.css('fontSize'), 10 );

switch (this.id) {

case 'switcher-large':

num *= 1.4;

break;

case 'switcher-small':

num /= 1.4;

break;

default:

num = parseFloat(defaultSize, 10);

}

$speech.animate({fontSize: num + 'px'},

'slow');

});

});

The extra properties allow us to

create much more complex effects, too. We can, for example, move an item

from the left side of the page to the right while increasing its height

by 20 pixels and changing its border width to 5 pixels.

So, let's do that with the<div id="switcher"> box. Here is what it looks like before we animate it:

With a flexible-width layout, we need to compute the distance that the

box needs to travel before it lines up at the right side of the page.

Assuming that the paragraph's width is 100%, we can subtract the Text Size box's width from the paragraph's width. While jQuery's .width()

method would usually come in handy for such calculations, it doesn't

factor in the width of the right and left padding or the right and left

border. As of jQuery version 1.2.6, though we also have the .outerWidth()

method at our disposal. This is what we'll use here, to avoid having to

add padding and border widths as well. For the sake of this example,

we'll trigger the animation by clicking the Text Size label, just above the buttons. Here is what the code should look like:

$(document).ready(function() {

$('div.label').click(function() {

var paraWidth = $('div.speech p').outerWidth();

var $switcher = $(this).parent();

var switcherWidth = $switcher.outerWidth();

$switcher.animate({left: paraWidth - switcherWidth,

height: '+=20px', borderWidth: '5px'}, 'slow');

});

});

Note that the height property has += before the pixel value. This expression, introduced in jQuery 1.2, indicates a relative value. So, instead of animating the height to 20 pixels, the height is animated to 20 pixels greater than the current height.

Although this code successfully increases the height of the<div> and widens its border, at the moment the left position cannot be changed. We still need to enable changing its position in the CSS.

Positioning with CSS

When working with .animate(), it's

important to keep in mind the limitations that CSS imposes on the

elements that we wish to change. For example, adjusting the left property will have no effect on the matching elements unless those elements have their CSS position set to relative or absolute. The default CSS position for all block-level elements is static, which accurately describes how those elements will remain if we try to move them without first changing their position value.

A peek at our stylesheet shows that we have now set<div id="switcher"> to be relatively positioned:

#switcher {

position: relative;

}

With the CSS taken into account, the result of clicking on Text Size, when the animation has completed, will look like this: