1. INVOKING OTHER DEVICE CAPABILITIES

You may have gotten the impression that everything you build

for a mobile website is somehow a limited facsimile of its desktop peer.

But rather than thinking of a mobile browser as being a poor cousin,

don't forget the things that mobile devices can uniquely do — after all,

their primary role is as communication devices that are far more

adaptable and personal than desktop computers.

A simple way to integrate

your mobile website with other capabilities of the user's handset is

through hyperlinks. If your mobile site contains a telephone number, for

example, what would be more natural than to click the number to start a

call to it?

Some mobile

browsers automatically parse the page looking for likely telephone

numbers and create links that launch the telephone dialer on the

handset. Both Apple iPhone and Android devices do this, although with

varied behavior: The former is fairly zealous at finding numbers in a

page (some of which may not, of course, be callable at all). The latter

seems to miss international formats of numbers and doesn't actually

highlight a number that is callable until the cursor focus falls on it.

It is more reliable, as a web

developer, to explicitly indicate when you want a numeric link to be

callable. Both iPhone and Android's automatic detection can be disabled

in the <head> part of the document with this string:

<meta name="format-detection" content="telephone=no">

telephony.html

Creating explicit links to

telephone numbers uses the tel: URI scheme, very similar in concept to

the mailto: scheme used to create links on desktop browsers to send

e-mail.

Call this number now: <a href="tel:15556661972">1-555-666-1972</a>

In fact, it's not necessary

to have the same number or text in the attribute as in the text of the

link itself, although it is probably advisable to do so. Users are

prompted to initiate the call, and they want confidence that the same

number is called as appears on the page, and not, say, a premium-rate

number.

Encouraging the user to send

SMS messages as a quick and easy alternative to e-mail is also possible

through the use of the sms: URI scheme. It has a similar syntax to tel:,

but theoretically allows you to specify the preferred body with which

you would like to pre-populate the user's composed SMS, like this:

<a href='sms:15556661972?body=Please%20send%20more%20details'>Contact you</a>

Not all devices honor the body text portion, although the links as a whole are widely supported.

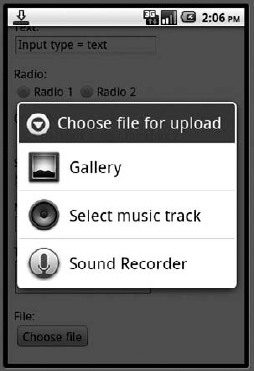

From platform to platform,

various browsers support other types of integration with native device

functionality. The iPhone supports links that invoke the native Google

Maps and YouTube apps on the device, for example, and Android supports

audio recording as part of its <input type='file'/> behavior (as shown in Figure 6-36).

However, unless you know for

sure that these proprietary implementations are broadly supported by

your target users' handsets, they remain somewhat unpredictable. As a

web developer, it is worth keeping up to date with developments in HTML5

implementations and BONDI-like standards to understand how best to hook

more intimately into mobile device functionality and in a

standards-based way.

2. THE STATE OF JAVASCRIPT

Although JavaScript is used extensively on

desktops to create everything from gimmicky animations to full-fledged

web applications, at the time of this writing it is still in a somewhat

adolescent phase on mobile: Full of promise and possibility, but as yet

used sparingly, if at all, on most mobile sites.

JavaScript is still very much

a technology you would rely upon only when you know the requesting

device has a well-featured browser — and probably one that is

WebKit-based. As a syntax, its constructs are fairly consistently

supported, but the diversity that you are likely to encounter concerns

the language's APIs into the web page's Document Object Model (DOM) —

which is, after all, the main point of using it in the first place.

Another challenge with

JavaScript is that relying on it is an all-or-nothing decision. In CSS,

for example, a device failing to support some particular selector or

property is not necessarily the end of the world: The user's experience

probably degrades to some default styling instead. But if a JavaScript

call does not behave correctly or throws an unhandled exception, the

entire interactivity (and perhaps, in turn, purpose) of a website can

grind to a halt.

For a sense of how

carefully you should tackle the addition of JavaScript interactivity to

your mobile site, consult the support tables on the excellent Quirksmode

site at http://quirksmode.org,

whose owner, Peter-Paul Koch, compiles excellent tests and results for

the behaviors of both desktop and mobile browsers. As an example, you

learn there that the JavaScript DOM method getElementsByClassName()

is not supported by hundreds of millions of Symbian handset browsers.

If, as is a commonplace pattern, you want to use CSS classes as a way of

indicating the interactive behaviors that should apply to certain

elements in the page, you need to test this behavior extensively and

consider other techniques to this method for binding behaviors to your

documents.

The DOM event model is also of

great interest for web developers, because it is the way in which user

actions can trigger interactivity to occur. Mobile browsers' event

models vary from those on the desktop, if only because those events that

relate to mouse gestures (such as mouseover or mousemove,

for example) may have no meaning when there is no cursor, and because

they need to introduce different events that relate to touch and swipe

behavior (such as touchstart and touchmove).

AJAX, by which is meant the

concept of sending asynchronous requests back to the server while the

web page is still displayed to the user, is a powerful and valuable

concept in the mobile context. It allows you to save the bandwidth and

latency impact of reloading a whole page when a form or data is

submitted, and it makes the user interface appear responsive to the

user. Nevertheless, its usage is again risky, and you should rely on

AJAX functionality only if you can be sure that the user's device

supports the XmlHttpRequest API well (as most WebKit browsers do), or

you have a good AJAX-less fallback mechanism that means the user can use

the site without it.

If this section has

discouraged you from trying to use JavaScript to enhance the

capabilities of your site, then it should be stressed that this is a

constantly evolving area of contemporary mobile web development, and the

state-of-the-art is never static. Recent exciting developments involve

the emergence of commitments to mobile from major JavaScript framework

authors — common libraries that have helped developers mitigate the

challenges of browser diversity in the desktop world and that look set

to tackle the same problems for mobile.

jQuery, a particularly

strong open-source JavaScript library, is currently developing built-in

support for mobile and intends to support a wide range of browsers, from

WebKit-based iPhone, Android, and Palm browsers to BlackBerry and Opera

Mobile. An advantage of jQuery for mobile is that its popularity on the

desktop means the ability to use much of the existing code and many of

the third-party plug-ins already available for its desktop

implementation.

Another library, the

commercially licensed Ext JS, has recently been relaunched as Sencha and

has released a dedicated mobile library designed to build rich

native-like applications on high-end touch devices, although currently

only of the Android and iPhone flavors. Finally, a number of smaller,

platform-specific JavaScript libraries are available, such as jQTouch

(which uses jQuery to build slick iPhone-based applications) and

iWebKit.

Hopefully, it is only a matter

of time before similar libraries emerge for other platforms or that

work across different devices and elegantly degrade accordingly.