Whether you are upgrading an existing AD

infrastructure or building a new one from the ground up, it is

important to properly plan your deployment. For our discussion, we will

focus on new deployments, however, we will note some specifics you

should be aware of when upgrading your domain to Windows Server 2008 R2

AD.

1. Active Directory Basics

Before jumping into your design, it is important

that you have a basic understanding of the architecture and how AD

works behind the scenes. It is important to remember that AD is not

only a security service for your network but also a database containing

configuration information about your network. For example, Exchange

Server 2007 and 2010 store critical configuration data in AD. This

ensures that critical application data can be highly available and

protected by geographic resilience.

Active Directory domain controllers

All DCs contain a copy of the AD database.

The Active Directory data store

The AD database is saved in a file on every DC in

the domain. The AD database is stored in the NTDS.DIT file located in

the NTDS folder of the system root, usually C:\Windows. AD uses a

concept known as multimaster replication to ensure that the data store

is consistent on all DCs. This process is known as replication.

There is no single master copy of the AD data store,

thus, each DC (except for Read-Only domain controllers (RODCs)) can

read and write to the data store. The replication process ensures that

all DCs have the newest copies of any changes made to AD. Multimaster

replication allows administrators to make changes on any DC in the

domain and be confident that those changes will replicate to all other

DCs.

Active Directory partitions

AD is broken down into three partitions that must be replicated to all DCs:

Domain partition

—The domain partition includes data related to the AD domain. It

includes objects such as users, groups, computers, and printers.

Schema partition

—The schema partition contains the attributes and classes that make up

the AD schema. These attributes define what type of data is stored in

AD and how that data is linked to other AD objects. For example, the

schema contains a first name field that is used to store the first name

for every user account in the domain. Think of the AD schema like the

fields in a database table.

Configuration partition —The configuration partition includes information about the configuration of AD such as domain and forest settings.

|

Extending the Active Directory schema

The AD schema is extensible, which means new classes

and attributes can be added by performing an AD schema extension.

Various applications, including Microsoft Exchange Server and Office

Communications Server, require extending the AD schema before they can

be installed on your network. Typically, you can identify a schema

extension file by an ldf extension at the end of the name. Ldf files

typically contain all of the schema changes for a given update.

|

|

Planning to extend the Active Directory schema

It is very rare that the process to extend the AD

schema fails. However, it is important to understand that schema

extensions are irreversible. New additions to the schema cannot be

deleted but only disabled. Though this is usually a low-risk process,

you should always test schema extensions in a lab prior to deploying

them in production.

|

2. Planning for Active Directory forest and domains

During the early stages of your AD planning, you

need to consider how many forests and domains will be needed to support

your network. To properly plan your forests and domains, you need a

clear understanding of each of them and how they apply to an AD

deployment.

Domains —A

domain is the base foundation of an AD hierarchy. AD domains contain

objects such as users, computers, groups, and printers. One or more

domains make up an AD deployment.

Trees

—A tree is composed of one or more domains arranged in a hierarchical

fashion. Trees are made up of a parent domain and one or more child

domains. The child domains share a contiguous namespace with the parent

domain. This means the child domains are named by prepending a domain

name to the fully qualified domain name (FQDN) of the parent. For

example, a parent domain name may be fabrikam.com. The child domain

would then be called northamerica.fabrikam.com.

Forests

—A forest is a collection of one or more trees. Forests use different

FQDNs. Forests maintain their own security but provide interaction

between all domains in the organization. All domains in a forest have a

two-way, transitive trust.

Active Directory trust relationships

Trust relationships allow administrators in one AD

domain assign permissions to users and groups in another domain and

vice versa. For example, a trust relationship could be established

between contoso.com and frabrikam.com. If a two-way trust is

established, then administrators in contoso.com could give users from

frabrikam.com access to resources in the contoso.com domain. Trust

relationships come in the following types:

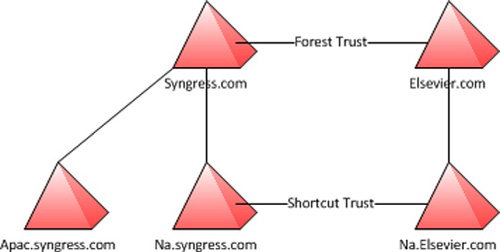

Forest trust

—A forest trust is a trust relationship established between two

separate forests. This allows all domains in a forest to trust all

domains in another forest. Forest trusts are transitive which means if

domain A trusts domain B, and domain B trusts domain C, then domain A

automatically trusts domain C.

Shortcut trust

—A shortcut trust is a manually created trust between two domains. This

is also transitive. A shortcut trust can be useful when dealing with

complex trees from multiple forests. Shortcut trusts can be set up

between child domains (see Figure 1) to improve log-on performance between the two domains.

External trust

—An external trust is a traditional trust relationship meaning, a trust

relationship can be setup between domain A and domain B but does not

automatically include domain C in the trust relationship. External

trusts can be one-way or two-way.

Realm trust

—A realm trust can be set up to provide a transitive or nontransitive

trust between a Windows Server 2008 R2 domain and another Kerberos v5

compliant realm such as UNIX or Linux environments. This trust can be

one-way or two-way.

There

may be situations where multiple domains will be required due to

security or ownership requirements. One example of this is during

acquisitions of other companies. Your company may acquire another

company that already has an AD domain. In situations like this, you may

need to build a trust relationship to allow users from your domain to

have access to data in the acquired domain and vice versa.

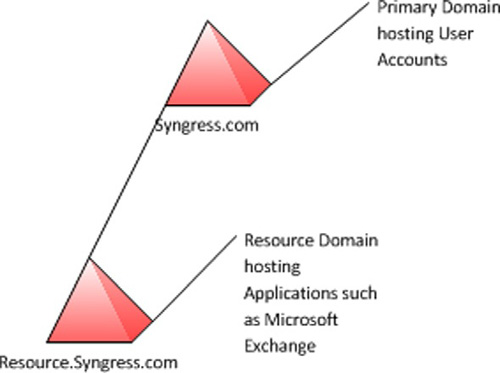

You may also consider the usage of a resource

forest. This is when you deploy an application, such as Microsoft

Exchange Server, into its own domain (see Figure 2).

This allows for better segregation of permissions as Microsoft Exchange

exists in one domain, while the Exchange users reside in another. This

provides a security boundary for administrators.

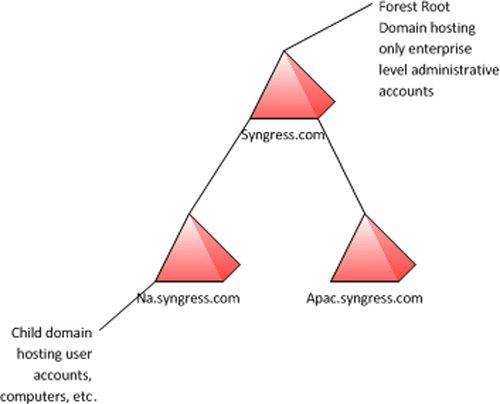

Another

scenario where multiple domains may be required is if you want to

create what is known as an empty forest root. An empty forest root

provides an additional layer of security, as all forest level accounts

are stored only in the forest root, while all other users, computers,

and various other objects are stored in the child domain(s). Figure 3 depicts an empty forest root deployment.

The specifics of how many domains and forests you

deploy will vary between organizations. If you have a somewhat simple

environment with a single group which needs to own the AD domain, you

may want to consider sticking with a single domain. This provides less

complexity than multiple domains and a single domain has been shown to

easily support up to a million objects (users, computers, etc). If you

administer a more complex environment where more security boundaries

need to be implemented or there is more political concern around who

can manage what, you may need to look at deploying multiple domains. Be

sure to thoroughly plan this prior to deploying AD.