The reputation Windows has as an audio playback and

editing platform has been, not to put too fine a point on it, abysmal.

There have been some improvements over the years. For example, the early

audio infrastructure (often called the audio stack)

seen in Windows 3.1 (16-bit) and Windows 95 (32-bit) supported only one

audio stream at a time, but Windows 98 enabled multiple playback

streams using the Windows Driver Model architecture. However, Windows

audio has always suffered from three major problems:

A poor interface for controlling audio and for troubleshooting audio problems—

Tools such as Volume Control, the Sound Recorder, and the Control Panel

Sounds and Audio Devices icon had difficult interfaces and limited

functionality, and clearly weren’t geared for the day-to-day audio tasks

that users face.

Poor quality playback and recording—

The Windows audio stack has always been merely “good enough.” That is,

audio in Windows—particularly playback—was constructed to give the

average user a reasonable level of quality. However, the default Windows

audio had nowhere near the fidelity audiophiles and professional audio

users require, so these users spent much of their time working around

inherent audio limitations (or giving up on Windows altogether and

moving to the Mac).

Poor reliability, to the point that audio glitches are one of main causes of system instability—

The problem here has been that much of the audio stack code runs in the

sensitive Windows kernel mode, where a buggy driver or process can

bring down the entire system.

To address these problems, the Vista audio team completely rewrote the

audio stack from the ground up. That’s good news for both regular users

and audiophiles because it means the Vista audio experience should be

the best yet. Completely revamping the audio infrastructure was a big

risk, but the aim was to solve the three previous problems. We’ll have

to wait and see whether Microsoft accomplished this ambitious goal, but

on paper, things look promising:

New tools for controlling the volume,

recording sounds, and setting sound and audio device properties

(discussed in the next three sections) offer a much improved user

interface geared toward common user tasks and troubleshooting audio

problems.

The new audio stack offers much higher sound quality.

Most audio code has been moved from kernel mode to user mode, which should greatly reduce audio-induced system instabilities.

Per-Application Volume Control

The Volume Control tool in previous versions of

Windows is a good example of poor audio system design. When you opened

Volume Control, you were presented with a series of volume sliders

labeled Master, Wave, Line In, CD Player, Synthesizer, Aux, and more.

For the average user,

most of these labels were, at best, meaningless and, at worst,

intimidating. What on earth does the Aux slider control? What’s the deal

with Line In? Most people ignored all the sliders except Master and

just used that slider to control playback volume. However, the Master

slider had problems of its own.

For example, suppose that you’re waiting for an

important email message, so you set up Windows Mail to play a sound when

an email message comes in. Suppose further that you’re also using

Windows Media Player to play music in the background. If you get a phone

call, you want to turn down or mute the music. In previous versions of

Windows, muting the music playback also meant muting other system

sounds, including your email program’s audio alerts. So, while you’re on

the phone, there’s a good chance that you’ll miss that important

message you’ve been waiting for.

The Windows Vista solution to this kind of program is called per-application volume control.

This means that Vista gives you a volume control slider for every

running program and process that is a dedicated sound application (such

as Windows Media Player or Media Center) or is currently producing audio

output. In our example, you’d have separate volume controls for Windows

Media Player and Windows Mail. When that phone call comes in, you can

turn down or mute Windows Media Player while leaving the Windows Mail

volume as is, so there’s much less chance that you’ll miss that incoming

message.

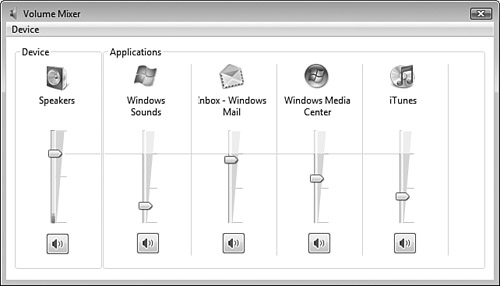

Figure 1

shows the new Volume window that appears when you click the Volume icon

in the notification area, and then click Mixer. The slider on the left

controls the speaker volume, so you can use it as a systemwide volume

control. The rest of the window contains the application mixer—this includes sliders and mute buttons for individual programs, and the program’s name and icon.

Note

How long an application’s slider remains in the

Volume Mixer window seems to depend on how often the application

accesses the audio stack. If a program just makes the occasional peep,

it will appear only briefly in the Volume Mixer and then disappear. If a

program makes noise fairly often, then it remains in the Volume Mixer

for much longer. So, for example, if you receive email messages all day,

you should always see the Windows Mail icon in the Volume Mixer.

In the old Volume Control tool, when you

adjusted the Master slider, the other volume sliders remained the same.

In the Vista Volume Control tool, when you move the speaker volume

slider, the program sliders move along with it. That’s a nice touch, but

what’s even nicer is that the speaker volume slider preserves the

relative volume levels of each program. So if you adjust the speaker

volume to about half its current level, the sliders in the application

mixer also adjust to about half of their current level.

Volume Control also remembers application

settings between sessions. So, if you mute Solitaire, for example, it

will remain muted the next time you start the program.

The new volume control also supports metering, in which the current audio output is displayed graphically on each slider (see Figure 7.3).

This metering appears as a green wedge that grows taller and wider the

louder the sound signal is. This is very useful for troubleshooting

audio problems because it tells you whether a particular program is

actually producing audio output. If you have no sound from a program but

you see the metering in program’s volume slider, the problem lies

outside of the program (for example, your speakers are turned down or

unplugged).

Note

Many notebook computers come with volume

controls that enable you to physically turn the computer’s speaker

volume up or down. Microsoft has talked about tying this physical volume

control into the Volume Control program so that if you turn down the

sound physically, the speaker volume slider would adjust accordingly.

This extremely useful feature was not implemented as I wrote this, but

it might appear in a later build of Windows Vista.

Sound Recorder

The Sound Recorder accessory first appeared in

Windows 95 and has remained a part of Windows ever since. Unfortunately,

the Sound Recorder in Windows XP is essentially the same program as the

original version, which means the program’s annoying limitations

haven’t changed, either:

Windows Vista comes with a completely new

version of Sound Recorder that does away with these limitations. For

example, you can save your recording using the Windows Media Audio (WMA) format, and there is no limit (other than available hard disk space) to the length of the recording.

Having no recording limit might sound dangerous

(long WAV files take up a lot of space), but the new Sound Recorder

captures WMA audio at a bit rate of 96Kbps, or about 700KB for a

one-minute recording. Compare this to a one-minute CD-quality recording

using the old Sound Recorder, which could easily result in a 10MB file!

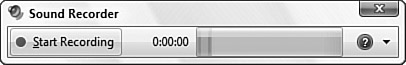

Figure 2

shows the new Sound Recorder window (select Start, All Programs,

Accessories, Sound Recorder). Click Start Recording to begin your

recording; click Stop Recording when you’re done. Sound Recorder

displays the Save As dialog box so that you can choose the file

location, name, and format.

Audio Devices and Sound Themes

The Windows Vista replacement for the Control

Panel Sound and Audio Devices icon is the Sound dialog box (select

Start, Control Panel, Hardware and Sound, Sound), shown in Figure 3.

The

Playback and Recording tabs show the playback and recording devices on

your system. The first thing to notice is that you now have a visual

reminder of the default devices for playback and recording in the form

of a green check mark icon, shown in Figure 3.

The check mark means that the device is the default for all uses.

However, you can also designate a device as the default. As shown in Figure 3, you can right-click a device and then click Set as Default Device.

Windows Vista also implements a more extensive

collection of properties for each device. Double-clicking a device

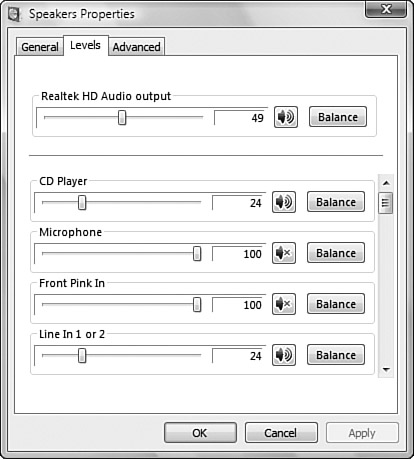

displays a property sheet similar to the one shown in Figure 4.

The properties you see depend on the device. Here’s a summary of the

tabs you see when you open the default playback device (although note

that not all audio playback devices support all of these tabs):

General— Change the name and icon for the device and any jack information disclosed by the driver

Levels— Set the volume levels

Advanced— Set the default playback format and latency and options for allowing applications exclusive control over the device