|

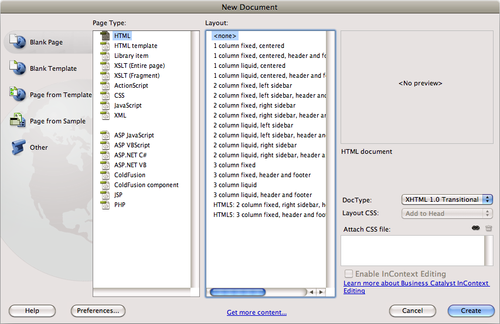

After you define a site, you’ll want to start building pages. Just choose File→New or press Ctrl+N (⌘-N on a Mac) to open Dreamweaver’s New Document window (see Figure 1).

It’s a little overwhelming at first. You have so many options it’s hard

to know where to start. Fortunately, when you just want to create a new

HTML file, you can skip most of these options.

To create a basic HTML file for a web page: From the left-hand list of document categories, choose Blank Page. The Blank

Page category lets you create a new empty document—maybe a web page or

something a bit more esoteric, like an XML file , an external JavaScript file, or one of the several server-driven pages, such as a PHP file . Both the Blank Template and “Page from Template” categories relate to Dreamweaver’s Template. The “Page from Sample”

category lets you choose from several files with already-created

designs. Most of the designs are old and left over from earlier versions

of Dreamweaver, aren’t very attractive, and don’t use the best

techniques for building a web page. However, Dreamweaver CS5.5 includes

some starter pages for creating mobile-only websites and web

applications. The last category, Other, lets you create documents for different

programming languages, like ActionScript or Java—unless you’re a Flash

or Java programmer, you probably won’t ever need these. From the Page Type list, choose HTML. You

can \ create other types of documents, too, most of which you’ll learn

more about later in this book, such as PHP pages for database-driven

sites, XSLT files for processing XML, templates, Library items, and CSS files . During

the tutorial in these pages—and, indeed, everywhere in

Dreamweaver—you’ll encounter a few terms frequently heard at web

designer luncheons: Root

folder. The first rule of managing a website is that every piece of the

site you’re working on—web page (HTML) documents, images, sound files,

and so on—must sit in a single master folder on your hard drive. This

folder is the root folder for your website, and because it’s on your computer, it’s called the local root folder, though Dreamweaver calls it your local site folder. The root

(a.k.a site folder) is the master, outer, main folder—think of it as

the edge of the known universe for that site: Nothing exists outside the

root. Of course, to help organize your site’s files, you can include

any number of subfolders within that main folder. When

you finish creating your site on your computer, you’ll move the files

in your local root folder onto a web server for the world to see. You

call the folder where you place your site files on the server the remote root folder. Local

site. The usual routine for creating web pages goes like this: You

create the page on your own computer—using a program like

Dreamweaver—and then you upload it to a computer on the Internet called a

web server, where your handiwork becomes available to the masses. So,

it’s very common for a website to exist in two places at once, one copy

on your computer and the other on the server. The copy on your computer is called the local site,

or the development site. Think of the local site as a sort of staging

ground, where you build your site, test it, and modify it. Because the

local site isn’t on a web server, the public can’t see it and you can

freely edit and add to it without affecting the pages your visitors see

(they’re on the remote site, after all). Remote site. When you add or update a file, you move it from your local site to the remote site. The remote,

or live, site is a mirror image of your local site. Because you create

the remote site by uploading your local site, the server folder has the

same structure as your local site folder, and contains the same files.

Only polished, fully functional pages go online to the remote site; save

the half-finished, typo-ridden drafts for your local site.

|

From the Layout list, choose “<none>.” This

choice creates a blank document. The other choices (“1 column elastic,

centered”, “1 column elastic, centered, header and footer”, and so on)

are predesigned page layouts. These designs (not to be confused with the

designs under the “Page from Sample” category) use CSS.

Because CSS-based layout can be tricky, Dreamweaver includes all the

code you need to create many of the most common types of page designs.

Select a document type from the DocType menu. Selecting a doctype,

or document type, identifies the type of HTML you’ll use to create your

page. It affects how Dreamweaver writes the HTML code and how a web

browser understands it. Fortunately, since Dreamweaver writes all the

code for you, you don’t need to worry about the subtle differences

between the different document types. XHTML 1.0 Transitional is the normal setting in Dreamweaver, but HTML 4.01 Transitional, HTML 4.01 Strict, and XHTML 1.0 Strict are also fine choices. The transitional

doctypes let you use a few HTML tags and properties that have been

phased out of the strict types. Most notably, transitional doctypes can use the “target” property for links—a simple way to force links to open in a new browser window. If

you don’t really understand or care about doctypes, just select HTML

4.01 Transitional. But make sure you avoid None (which can force

browsers to display pages in what’s called “quirks mode”

and makes perfecting designs difficult), XHTML Mobile, and XHTML 1.1

(which is not only obsolete, it also requires a special setting on your

web server to work properly). If

you like to live on the technological edge of web development, you can

choose HTML5. HTML5 offers a simplified document type, plus a whole

range of new HTML tags and features. Unfortunately, Dreamweaver CS5.5

doesn’t offer ready access to these new HTML5 tags or features—in other

words, you won’t find any of the new tags in the Insert panel, or tools

for using cool new features like the <canvas> tag for drawing on a

web page.

Tip: If

you don’t want to deal with the New Document window every time you

create a page, choose Edit→Preferences in Windows

(Dreamweaver→Preferences on a Mac). In the Preferences dialog box, click the New Document category and then turn off the “Show New Document Dialog on Control-N” checkbox. While

you’re at it, you can specify the type of file Dreamweaver creates

whenever you press Ctrl+N (⌘-N). For example, if you usually create

plain HTML files, choose HTML. But if you usually create dynamic pages,

choose a different type of file—like PHP, for example. With

these settings, pressing Ctrl+N (⌘-N) instantly creates a new blank

document of your choosing. (Choosing File→New, however, still opens the

New Document window.)

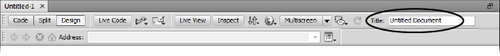

Click Create. Dreamweaver opens a new, blank web page ready for you to save and title (see Figure 2).

Choose File→Save. The

Save As dialog box appears. You need to save the file somewhere inside

your local root folder. You can save it inside any subfolder within the

root folder as well. Type a name for the file and then click Save. Make

sure the name doesn’t contain spaces or any characters except letters,

numbers, hyphens, and underscores, and that it ends in either .html or

.htm. Although most operating systems let you save files

with long names, spaces, and characters like #, $, and &, some

browsers and servers have trouble interpreting anything other than

letters and numbers. Furthermore,

web servers rely on file extensions like .htm, .html, .gif, and .jpg to

know whether a file is a web page, graphic, or some other type of file.

Dreamweaver for Windows automatically adds the extension to your saved

document names. But on the Mac—which lets you save files without

extensions—make sure the file ends in the suffix .html or .htm when you

save it. At the top of the document window, click inside the Title box and then type a name for the page. Every

new document Dreamweaver creates has the unflattering title “Untitled

Document.” If you do a quick search on Google for “Untitled Document,”

you’ll find (at the time of this writing) 27,500,000 results (obviously

there are still some people who need to pick up a copy of this book).

Dreamweaver probably created most of those pages. You should change this

to a descriptive title indicating the main topic of the page, like

“Contact Chia Vet,” “About Chia Vet’s Chia Pet Services,” or “Technical

Specifications for the Anodyne 3000 Indoor Lawn Mower.” Not only is

replacing “Untitled Document” more professional, but providing a

descriptive title can improve a web page’s ranking among search engines.

|