Although project management might overlap other types of management, it entails a specific set of management processes.

1. What Is a Project?

Organizations perform two types of work: operations and projects. A great way to define a project is to say what it is not, and a project is not an operation. An operation is a series of routine, repetitive, and ongoing tasks that are performed throughout the life of the organization.

Operations are typically necessary to sustain the business. Examples of

operations are accounts receivable, employee performance reviews, and

shipping and receiving. Employee performance reviews might take place

every six months, for example, and although the names and circumstances

of employees and supervisors might change, the process of preparing and

conducting employee reviews is always the same. In addition, it’s

expected that employee reviews will be conducted throughout the life of

the organization.

On the other hand, projects

are not routine or ongoing. That is, projects are unique and temporary

and are often implemented to fulfill a strategic goal of the

organization. A project is a series of tasks that will culminate in the

creation or completion of some new initiative, product, or activity by a

specific end date. Some examples of projects include an office move, a

new product launch, the construction of a building, and a political

campaign. The same project never occurs twice—for example, this year’s

product launch is different from last year’s product launch. There’s a

specific end date in mind for the launch, after which the project will

be considered complete. After the project is complete, a new and unique

product will be on the market.

Projects come in all sizes.

One project might consist of 100 tasks; another, 10,000. One project

might be implemented by a single resource; another by 500. One project

might take 2 months to complete; another might take 10 years. Projects

can contain other projects, linked together with a master project

consolidating them all. These subprojects, however, are all unique and

temporary, and they all have a specific outcome and end date.

2. What Is Project Management?

Project management is the coordinating effort to fulfill the goals of the project. The project manager,

as the head of the project team, is responsible for this effort and its

ultimate result. Project managers use knowledge, skills, tools, and

methodologies to do the following:

Identify the goals, objectives, requirements, and limitations of the project.

Coordinate

the different needs and expectations of the various project

stakeholders, including team members, resource managers, senior

management, customers, and sponsors.

Plan,

execute, and control the tasks, phases, and deliverables of the project

following the identified project goals and objectives.

Close the project when it is completed and capture the knowledge accrued.

Project

managers are also responsible for balancing and integrating competing

demands to implement all aspects of the project successfully, as

follows:

Project scope Articulating the specific work to be done for the project.

Project time Setting the finish date of the project as well as any interim deadlines for phases, milestones, and deliverables.

Project cost Calculating and tracking the project costs and budget.

Project human resources Signing on the team members who will carry out the tasks of the project.

Project procurement Acquiring the material and equipment resources, and obtaining any other supplies or services, needed to fulfill project tasks.

Project communication Conveying assignments, updates, reports, and other information to team members and other stakeholders.

Project quality Identifying the acceptable level of quality for the project goals and objectives.

Project risk Analyzing potential project risks and response planning.

While project managers might

or might not personally perform all these activities, they are always

ultimately responsible for ensuring that they are carried out.

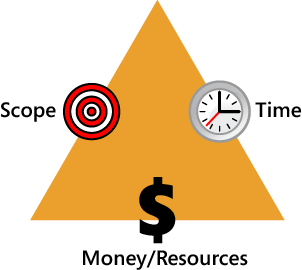

Balancing

scope, time, and money is often among the biggest responsibilities of

the project manager. These factors are considered the three sides of the

project triangle. (See Figure 1.)

|

Project

2010 supports many but not all of the management areas associated with

project management. That is, while Project 2010 does a great job with

project time and cost, it provides only glancing support for project

procurement and project quality.

However, you can combine

Project 2010 with other tools to create for yourself the full package of

project management support. Use Project 2010 to capture the lion’s

share of project information, including the schedule, milestones,

deliverables, resources, costs, and reporting. Then draw upon other

tools when needed to more fully handle responsibilities specifically

associated with procurement or quality. Finally, come full circle with

Project 2010 by adding notes to tasks or resources, inserting related

documents, or hyperlinking to other locations.

For example, use Project

2010 to help estimate your initial equipment and material resource

requirements. Work through your organization’s procurement process and

compile the relevant data. Add the equipment and materials as resources

in your project plan and add notes as appropriate, making the

information easy to reference. Use a tool such as Microsoft Excel 2010

to help track the depletion of materials to the point where reorder

becomes necessary. Even though Project 2010 can’t manage every aspect of

your project, it can still be the central repository for all related

information.

|

If you increase the scope, the

time or money side of the triangle will also increase. If you need to

reduce time—that is, bring in the project finish date—you might need to

decrease the scope or increase the cost through the addition of

resources.

|

There’s some debate about

how to accurately describe the key controlling elements that make up a

project. Some believe that a project is best described as a triangle—the

three sides representing scope, time, and money. Others say that it’s a

square—with scope, time, money, and resources being the four sides,

each one affecting the others. Additional debate suggests a hexagon of

scope, time, money, resources, quality, and risk.

|

Whether

you keep the project triangle, rectangle, hexagon, or other shape in

mind as you manage your project depends largely on the priorities and

standards set for your project and by your organization, and on the

weight placed on certain demands over others. Knowing these priorities

and standards can help you make appropriate decisions about the project

as the inevitable issues arise. Although scope, time, and cost tend to

be the most prevalent demands, the following is the full list of project

controls:

Scope

Human resources

Quality

Time

Procurement

Risk

Cost

Communications

These project controls are also referred to as project knowledge areas.

An additional knowledge area is project integration

management—balancing the demands of these other project controls to

succeed in meeting the goals of the project.