1. WBS, Phases and Control Points, Methodologies, and Life Cycles

Many of the preceding terms are used by project

managers to describe the approach that is used to define and execute a

project. Each of these has been explained in many other texts and

references.

Before building any schedule, the project

manager must consider two key components: work decomposition (what work

needs to be done, the Work Breakdown Structure or WBS) and managerial

control (stages, phases, and life cycle requirements). The discipline

used for either will depend on the environment in which the project is

executed, so the formality will vary, but both components must be

considered. The tasks or activities and milestones (how the work will be

accomplished) should not be defined in a project schedule until the WBS

and control framework are determined. WBS helps the project manager set

parameters around the scope of work to be done; the life cycle sets the

controls in place for decisions during project execution. If these two

components are kept in control, the project will have a much higher

opportunity for success.

Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

Step

one in building a schedule is to begin with a Work Breakdown Structure

(WBS) that allows decomposition of the scope of the project from major

components to the smallest set of deliverables, called work packages.

As a best practice, this process is completed before a true schedule is

built. It can be done using Microsoft Project as long as ongoing “use”

rules are defined and followed to keep the WBS components intact after

the project is approved and baselined.

If the scope of your project is managed through a

WBS, all the tasks and milestones will be created in support of specific

work packages and can be rolled up through the structure for tracking

progress using Earned Value Management techniques. This practice

eliminates some of the common failure points in project management, such

as scope creep and fuzzy requirements. All work is clearly linked to

the production of a deliverable, and progress against that deliverable

can be monitored.

Managerial Control

So many terms are used in the context of managerial

control that a few definitions are in order. Hundreds of resources are

available to provide detailed explanations; the purpose here is context

only. The hope is that these simple descriptions will help the user’s

understanding when building a project schedule, as discussed in the

following sections.

Phases and Gates

Many organizations have established processes for

deciding what projects will be approved and for overseeing the projects

after they have been launched. In some organizations, the processes are

rigorous and robust; in others, the processes might be simple guidelines

that have been put in place to help project managers. In either case, a

defined set of standard phases and control points (often called gates)

simplify the decisions that need to be made when running a project. In

most cases, templates can be created that standardize the phases and the

required control points for different types of projects.

Phases and gates can allow more management control of

the project, as they break down the project into smaller components.

This helps to keep executive and team focus aligned on the same set of

activities. A change between phases is usually defined by some kind of

transfer. In many cases, the transfer requires a formal review before

the project is allowed to move into the next phase. It is not unusual,

however, for phases to begin before the completion of the previous

phase, especially when the risks are judged as acceptable. Each

organization will make its own determination of the level of control

required.

Building

the phases and control points into templates is an excellent way to

minimize the amount of work that needs to be done when building a new

schedule. Many examples are already available in Microsoft Project, and

the organization can build additional ones as needed.

Methodologies

As organizations mature in the project management

discipline, they very often adopt more formal management control

systems. These systems are typically described as methodologies that

include processes, rules, standards, and methods for how work will be

done. In this section, we identify a few of the ones used in specific

industry segments.

Life Cycles

Like methodologies, project life cycles are unique to

the industries and disciplines in which they are used. Although all

projects have a beginning and an end, they will vary greatly in how the

work is accomplished. It is nearly impossible to define an ideal life

cycle. Some companies and organizations use a single, standardized life

cycle for every project, whereas others permit the project manager to

choose the best life cycle for the project. In others, a variety of life

cycles exists to accommodate different levels of complexity and

different styles or types of work.

Regardless of the organization’s choices

regarding methodologies and life cycles, all organizations can make use

of a scheduling tool to help with project execution. The key to success

in every case is that the schedule must be focused on the deliverables

to be produced rather than the process. The process must be set up to

assist with producing deliverables.

2. Using Microsoft Project with Methodologies and Life Cycles

Almost all organizations have at least a small number

of technology projects underway, so software development is an

excellent example of the wide variety of project-scheduling approaches

available to organizations. The types of projects range from simple to

complex, short to multiyear, and goal-oriented to open-ended research.

The following examples discuss the associated software development life

cycle (SDLC) and how Microsoft Project can be set up to support the life

cycle. As you review the examples, you should also keep in mind that

these projects should be planned and executed using the principles

described in the previous sections on project standards (the PMBOK Guide

and PRINCE2). Although strict adherence to the standards is not

required or necessary on every

project, it is useful to remember that there are five major process

groups to be managed on each project and that there are nine knowledge

areas that should be considered throughout the project’s life cycle.

Waterfall Development Process

Traditional software development is often described

as a waterfall model because it is sequential in nature. The assumption

with this model is that phases can be completed in order with little or

no need to repeat the previous activities. Development is described as a

waterfall, steadily falling down through traditional phases such as

definition, preliminary design, detailed design, coding, testing,

implementation, and transition to operations.

This method of development is used in many

organizations today, especially those involved in multiyear programs.

The phases can be lengthy and the work can be very exacting. Although

the name suggests that all work from one phase is completed before

moving into the next phase, these types of projects are often set up

with overlapping phases so that design can begin on certain deliverables

as soon as the definition of the work for those deliverables is

completed. In addition, there is typically some level of iterative

development involved in almost all projects but the term “waterfall” is

still in common use today.

In this type of project, the tendency is to set up

the project schedule in the same order as the major phase names.

Instead, the project can be set up so that it is broken into logical

work packages that can be monitored and measured separately.

Iterative Development

Iterative development provides a strong framework for

planning purposes and also flexibility for successive iterations of

software development. The Rational Unified Process (RUP) and the Dynamic

Systems Development Methods are two frameworks for this type of project

life cycle. RUP is not only a methodology for software engineering

project management; it also has a set of software tools for using the

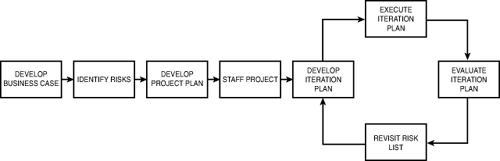

specific methodology that is the Rational Unified Process. Figure 1 depicts the RUP workflow.

The

goal for this type of software development life cycle (SDLC) is to

allow the developers to learn through incremental development and the

use of prototypes instead of trying to complete detailed requirements

before the development work begins. Agile and XP can also be considered

to be iterative methods.

Agile Development Process

Agile is a philosophy of project management that

moves away from the classic project management methods and focuses less

on planning and more on execution. In Agile, crucial decisions are made

during the project execution phase, instead of the planning phase. As

business and project environments become more fluid and dynamic, the

amount of time for effective planning becomes less and less. This does

not mean that planning will be ignored; rather, the focus shifts to

supporting decisions during project execution instead of finalizing all

decisions during the planning stage.

Agile is not an all-or-nothing methodology either; it

is possible to combine Agile with more classic project management

ideas. Whereas classic project management is comprehensive and works in

diverse situations, Agile can add various ideas for facing new and

unique situations that can be found in creative, knowledge-based

industries.

Here are some of the attributes of an Agile SDLC:

Short development cycles are used to produce working software in weeks rather than months.

Communication between the business users and the developers occurs daily.

Documentation

of working functionality is captured after the software is completed;

there is limited documentation of the requirements or design.

Timeboxing is used to force tough decisions early in the project.

Changes to requirements are expected; they are a result of early working prototypes and are a goal of the process.

The

project manager for an Agile team is focused on ensuring excellent

communication as the primary mechanism to maintain progress.

Agile development can be difficult for large

organizations to embrace because it does not require a focus on formal

planning of an entire project. The use of Agile should not be used as an

excuse to avoid planning or managing a budget. The approach is meant to

provide a lighter and faster method to reach a goal, but the goal is

still required. The major difference is that the primary measurement of

progress is frequent delivery of small amounts of working software. With

a focus on feature delivery, it can sometimes be difficult to

understand the overall picture, so strong project management must

provide this clarity.

In this type of environment, a project team can still

use Microsoft Project to support its goals. In an Agile environment,

the tool is not used to develop a robust schedule with a

beginning-to-end flow of tasks and resources. Its use in this case

supports communication to management and ensures that changes are

captured and the backlog of work is moved through each successive

iteration of the project schedule. In the following example, the project

manager has established a budget summary task to provide rollup of

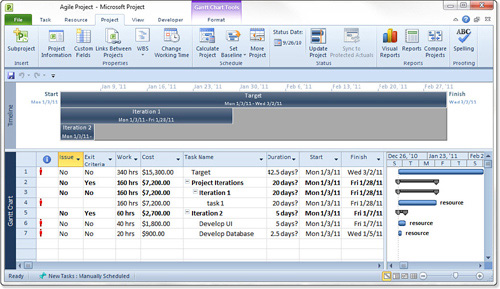

budget for management purposes. Successive sets of work are defined in small iterations, while the overall timeframe and budget are obvious for all (see Figure 3.4).

This approach enables the team to perform iterative planning while

still meeting the business requirements of not exceeding a specific

timeframe and budget. By establishing a project schedule with an overall

goal, the needs of the team and their management can be met. Refer to Figure 2

for an example of a short project that is expected to complete within a

target effort of 340 hours. The work is not fully defined at the

beginning so that the team has the flexibility to decide what work will

happen in what order. Management is still able to see overall metrics of

planned work, actual work, and the current estimate of work remaining.

Agile is an extremely successful method of software

development that is very well suited to an environment with

self-motivated teams, open communications, and leadership that is

comfortable with a prototyping approach to work. It does not fit all

projects, but when it works, it works very well. The schedule created in

Microsoft Project for this type of approach becomes a tool for

communication, overall budget and time goals, and historical tracking

purposes.

Note

For organizations that use the

Project Server tool, this method enables them to use an Agile approach

and yet have oversight of the entire project portfolio. Agile projects

coexist with standard iterative projects in their Project Server

environment; the projects have planned timeframes, resources, and

budgets but are not required to have all the work scoped out at the

beginning of the project. |

Extreme Programming

Extreme Programming, or XP, is another method within

the Agile family that has become a simple and flexible way for

developing software through the writing of tests. It is designed to be

used by a group of two to ten programmers who are able to execute tests

in a fraction of a day. It uses short cycles of phases, with early

and continuing feedback during each cycle. This flexibility enables it

to respond to changing business demands through the implementation of

functionality. XP’s use of automated tests, written by the programmers

to scrutinize development, helps early detection of defects and also

enables the cycle of phases to evolve as the project continues. These

automated tests depend both on the short-term instincts of programmers

and also on the long-term interests of the project. It also relies

heavily on a system of oral communication, tests, and source code to

help communicate the system structure and intent. These processes allow

for the day-to-day programming of a feature, and then moving on to

testing, implementation, design, and integration, all packed into each

cycle.

The scheduling methods used in the preceding Agile example can again be adapted for XP.

Spiral Development Project

Spiral development was defined by Barry Boehm in 1985

and is often used in fairly large projects that take months to two

years or more to complete. The initial focus might be on core

functionality, and then the “bells and whistles” such as graphical user

interfaces and reporting are added at a later time. This is sometimes

considered to be another form of iterative development, but the

structure of the plans and schedule focus on a robust core design in the

early stages.

Research Project

A research project might be the most difficult type

of project to tackle when it comes to identifying a project schedule.

Often, there is no clear goal in mind, and there might not even be an

expectation of a specific end date or budget. On the other side,

however, even research projects must be funded by someone, and they must

have a working staff, so there is typically some expectation of a

result. In most cases, there is also an expectation that the funding is

used responsibly, so there must be a process in place to track how the

money has been spent.

Microsoft Project can once again be used to

support this type of project as a tracking mechanism and a place to

bring together the set of work that will be performed. The schedule will

not require all the advanced features of critical path analysis,

resource-leveling, and predecessor/successor relationships, but it can

be used as an easy method of historical support and a loose prediction

of the work that is to be accomplished.

3. Accommodating Teaming Styles

High-performance teams, self-managed teams, and other

nontraditional structures began to emerge more than 50 years ago in

Great Britain and gained acceptance across the globe as several large

corporations began to adopt the concepts. The general idea behind these

teaming styles was to loosen managerial constraints in an effort to

increase worker performance and make quantum leaps in accomplishment of

organizational goals.

When framed correctly, the teams need little

direction and excel in accomplishing the goals of their projects. If the

dynamics are not understood, however, little is accomplished. From a

project management perspective, Agile or XP projects can be a bit

intimidating because the team dynamics can overwhelm the designated

leader. In reality, successful self-managed teams are not leaderless.

They have simply figured out a mechanism to allow many people within the team to play a leadership role.

Even in a team where a project management role has

not been defined, someone must take on the job of setting a direction to

accomplish a goal. The goal might only be one week in the future, but

the team must coalesce around that goals, and the person who makes that

happen is a leader. If the project manager understands the dynamics of

the team, he or she can use these dynamics to improve the team’s focus

and increase its performance. The PM must be comfortable with sharing

decision making and needs to focus heavily on communication of

information within the team and with the stakeholders of the project.

Things change quickly in this environment, so communication of status

becomes a driving force for the project.

Microsoft Project is an excellent tool to

aid the PM in communication. Two components need to be established to

make this successful. The overall goal of the project needs to be clear

to the team, and the boundaries of the project (overall timeframe,

scope, resources, and budget) must be understood. If these components

are established within the tool as a baseline, the remainder of the

schedule can be flexible or rigid, as dictated by the project structure

and the teaming style.